This is for all you private-company employees out there who still have your job. And have exercisable stock options hanging over your head, causing persistent low-key anxiety about:

Should I be doing something with these?

[Note: If you’ve been laid off, this blog post isn’t for you. You could check out our article about exercising ISOs or letting them turn into NSOs after you leave a company. You might instead, of course, be facing the decision of exercising your options or losing them entirely. That’s a stressful decision. Worthy of its own blog post. A blog post I haven’t written. Yet.]

Leaving your job forces your hand when it comes to options. There’s a 90-day deadline to do something.

By contrast, while you’re still employed, you don’t have to do anything. You can just wait.

But maybe that’s the wrong approach. What to do! Sometimes people are paralyzed with indecision. Sometimes people basically close their eyes and leap into a big decision without truly understanding the risks and rewards of it.

We recently went through this exercise with a client at a large, pre-IPO, company that is doing quite well, even in these stressful times.

The client has so many options that exercising them all would be really expensive. But also, they felt pressure to maybe do something? Isn’t that what you do with options in private companies? It’s better to exercise them as early as possible, right?

Maybe. It really all does depend deeply on your personal financial situation and attitude towards risk. The “right” answer of course also depends deeply on what ends up happening with the company and its stock…but you have no control over or knowledge of that future event. You can only know your own personal financial and emotional situation.

High-Level Framework for Making This Decision

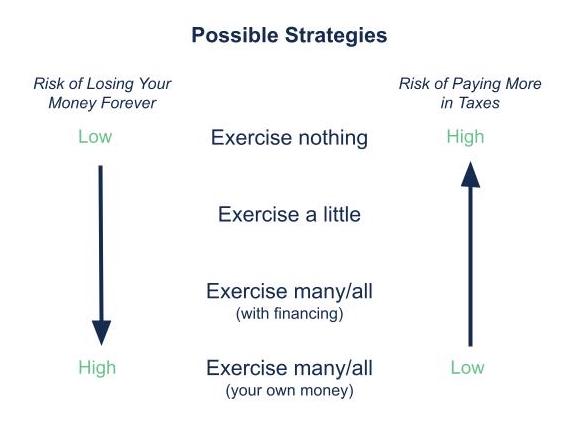

Making this decision boils down to one thing, in my opinion: balancing the tension between these two desires:

- Minimizing how much money you can lose

- Minimizing the tax rate you pay on any gains

As I see it, you have four basic choices when it comes to options at a private company where you can’t sell the stock once you own it:

- Exercise nothing and wait and hope for a liquidity event, before your options expire.

- Chip away very slowly by exercising as many options as you can each year, without incurring AMT (for ISOs) or incurring only a small and acceptable amount of tax (for NSOs). But mostly you’re waiting and hoping, as in above strategy.

- Get financing to exercise (and pay taxes on) many/all exercisable options now.

- Exercise many/all exercisable options per year, incurring/paying AMT

Keep in mind that this is not an all-or-nothing decision.

For the sake of brevity, I’m going to use the phrase “go public” throughout this post. What I really mean is any liquidity event: going public, getting acquired, having a tender offer…or something else I’m not thinking of now.

Some Simplifying Assumptions I’m Making

I am ignoring (the blog post can only be so long!) the possibility of exercising options and buying the shares when they qualify as Qualified Small Business Stock. If you are able to do this, then the future capital gains tax rate could be zero, which obviously is very very nice. If you can acquire stock from your company when it is a Qualified Small Business, then that argues for exercising instead of waiting.

I am assuming your options cost a meaningful amount of money to exercise. If your options are super cheap and there’d be no tax impact (which would be the case if the 409(a) value of the stock and your strike price are the same), then you can probably ignore all this neurotic thinking below. You could probably just exercise all of the options now and put very little of your money at risk. This usually only occurs in very early stage companies.

I’m ignoring the possibility that the options might expire, which they can do either due to the simple passage of time or because you’ve left the company.

Strategy #1: Exercise nothing, wait, and hope for a liquidity event before your options expire.

Look, the reason you exercise options before you have to (i.e., before they expire, which can happen when you leave the company or just if you’ve stuck around a really long time) is to get a lower tax rate on the hoped-for gains in the future.

As long as your options aren’t expiring, I am here to say: You can simply hold them!

Pros

You are not putting your own money at risk.

If your company doesn’t go public, you will not lose any money.

I’m telling you, as a financial planner who’s seen a lot of clients go through private companies of varying levels of success, this is a Very Reasonable Approach.

Cons

If your company eventually IPOs like a bad mamma jamma, and you exercise and sell, you will end up paying the higher ordinary income tax or short-term capital gain tax rate (the rates are the same, though the names of the taxes are different) on the gains instead of the lower long-term capital gains tax rate.

This sounds scary to many people! And maybe it is a big difference. Also maybe it’s not as bad as you fear. I encourage you to simply do some very basic, high-level arithmetic (not even “math”! Arithmetic) before you start knee-jerking “I don’t wanna pay higher taxes!”

In the IPO year, you’ll likely have a huge income. So:

- Your federal ordinary income tax rate and short-term capital gains tax rate will likely be 37% (the top rate).

- Your long-term capital gains tax rate will likely be 20% plus the 3.8% net investment income tax rate, for a total of 23.8%.

That’s 13.2% lower.

If you wait to exercise until you can sell your shares on the open market (i.e., your company has gone public), you will pay 13.2% more in taxes on the gains.

Maybe you think that’s a lot. Maybe that’s less than you thought it would be. But at least now you know the difference you’d actually deal with.

Strategy #2: Chip away slowly and avoid/minimize taxes.

You can put “just a little” money towards your options each year. So little that you probably won’t even feel it.

With ISOs, a reasonable (if arbitrary) threshold is to exercise as many ISOs as you can without incurring Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). To figure this out, you can either:

- Work with a CPA (my favorite answer for pretty much all tax questions)

- Use Carta’s or SecFi’s exercising modeling tools (for a less robust but more accessible tool). Carta’s tool is available only to people whose stock plans are administered by Carta. SecFi is available for free to everyone, though you do have to be willing to receive marketing emails from them in exchange for access.

With NSOs, you can choose a small-ish (for you) amount of money to commit to exercising the options each year, as you will owe taxes on the exercise. The difference between the strike price and the 409(a) will count as ordinary income, just like your salary.

But mostly you’re waiting and hoping, as in the above strategy, with the rest of your options.

Pros

You are putting minimal money at risk.

If your company doesn’t go public, you will not lose much money. You might not even feel it.

If your company does successfully go public, then at least you have some—albeit a small fraction of—shares that will get the lower tax rate.

Cons

If your company goes public, you’ll pay a meaningfully higher tax rate on many—not all—of your shares. In which case, you will end up with less money after-tax than had you exercised your options earlier.

Consider thinking of this approach as “the best of both worlds.” (The cynical among you could call it “the worst of both worlds.) A middle-of-the-road approach. I love middle-of-the-road approaches when it comes to things of such profound unknowability. I think it has the best chance of minimizing regret.

Strategy #3: Exercise (and pay taxes on) many/all of your options now, using financing.

By “financing,” I mean using the services of companies like SecFi, ESO Fund, Vested, and EquityBee. These companies will give you cash right now in exchange for a repayment later (when your company goes public, typically) of that loan along with a portion of the shares you own, if your company stock becomes valuable.

Typically these loans are “non-recourse,” meaning that if they loan you the money, and then your company goes <splat>, you don’t have to repay the loan.

Pros

You are not putting your own money at risk.

As long as you exercise early enough, you will get the lower, long-term capital gains tax rates on any gain in stock price between now and when you can sell your shares. If your company goes public successfully, you will save up to the above-calculated 13.2% lower tax rate (by current tax brackets) on your gains.

If you now own the shares, that means that you can contemplate leaving your job (or be laid off) without having to endure the added stress of “Should I fork over a ton of money to exercise these options within the next 90 days? Or lose them?” This is less relevant if your company’s stock plan agreement says that your options won’t expire after 90 days. Some more-“enlightened” companies give stock options a 10-year expiration date, regardless of whether you are still at the company.

And even though I said earlier that we’re assuming you’re not at risk of your options expiring, I’ll just say here that, by exercising now (which converts those options to shares you own), you now won’t lose options at the expiration date. (This benefit assumes your company doesn’t have a “clawback” provision in their stock plan agreement, which allows them to take back the shares, with payment, upon you leaving your company.)

Cons

You give up many of your shares to the financing company. The more successful the IPO is, the more valuable those forfeited shares are, the more painful it is.

Depending on the kind of financing, if your company does not successfully go public and the stock becomes worthless/worth less, the loan could be forgiven.

Here’s the kicker: that forgiven loan amount would be considered taxable ordinary income.

If the (forgiven) loan was for $500,000, then taxes could be roughly $190k (making lots of simplifying assumptions and using this simple calculator). With no valuable company stock to pay it with. You have an extra $190k lying around to pay in taxes, in exchange for stock that is worth bupkus?

In my opinion, you should consider using financing primarily if you’re leaving a company (whether you want to or not), when you have to exercise now or lose the options.

As long as you’re not at risk of losing options, you really don’t need to sacrifice a big percentage of the possible upside of your company stock to get financing. Taking the higher tax rate hit (by waiting) is likely better.

You really just have to compare the numbers: if the financing company wants 20% of your shares, but the extra tax would be “only” 13.2%, then waiting and paying the extra tax is better.

Unless you’re facing losing your options, financing probably costs too much.

Strategy #4: Exercise (and pay taxes on) many/all of your options now, with your own money.

This is the “maximum risk, maximum reward” strategy. You exercise a bunch (maybe even all) of your options, using your own money for both the strike price and the possibly hefty tax bill.

Pros

You get all the same benefits as Strategy #3 (financing) except, of course, you’re putting your own money at risk.

Cons

You are putting potentially a lot of your own money at risk. (“A lot” is a concept relative to your psychology around money and to the rest of your finances.) If your company does not successfully go public, you could lose up to all of it.

Have you endangered yourself by putting at risk more money than you could safely lose? Can you no longer afford to fund important goals in your life (e.g., taking a sabbatical, going back to school, buying a home, charitable donations)?

Money that you need for something important (either protecting yourself or giving yourself really important opportunities) is not money you risk in this way.

If you spend money on private company options, you have to assume you won’t see it again and plan accordingly.

Another Perspective: The Decision Has Asymmetric Risks and Rewards

As I was writing this blog post, I had a thought that was interesting enough (to me) to include it, even if it doesn’t help you make your decision. Maybe you’ll find it thought-provoking, too!

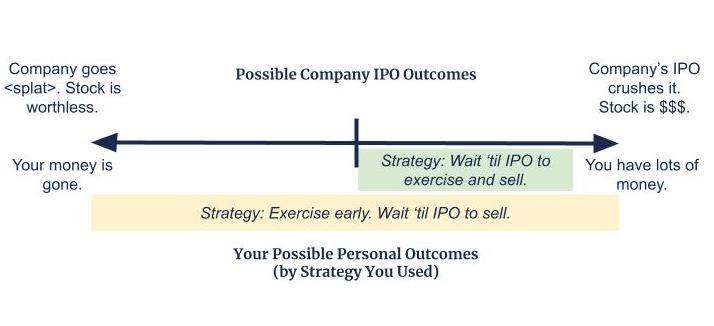

Note the asymmetry of risk and reward in this “Do I exercise or not?” decision:

Let’s say you exercise none now and retain 100% of your options, at no risk to yourself.

- If your company IPOs successfully, you will benefit 100% from that IPO. You will simply have a larger tax bite taken out of it.

- If your company doesn’t IPO successfully, you have lost no money.

Your outcomes will be “neutral” to “really good.”

You’ve narrowed the spectrum of possibilities for your money situation in the future. Yes, you’ve eliminated the best of the possibilities, but you’ve kept really good ones and eliminated all the bad ones. By narrowing the possibilities, you have also made your future less uncertain.

Versus

Let’s say you exercise a bunch of options now, putting a bunch of your money at risk.

- If your company IPOs successfully, you will benefit 100% from that IPO. You will also have a smaller tax bit taken out of it. Yes, you will end up with more money than had you waited to exercise.

- If your company doesn’t IPO successfully, you have likely lost a lot of money. (Hopefully not more than you could “afford” to.)

- Regardless of the outcome, you’ve just lost a lot of liquidity. What? That means you’ve spent that money now, so even if the IPO does happen successfully…eventually, until then, you have no access to the money you put into the exercise.

Your outcome could be anywhere from “Ohhhh, ouch, that’s bad” to “Whoo, gonna buy momma some new shoes! And then a yacht!” The spectrum of possibilities is vast, almost unconstrained.

This is a much more volatile, risky proposition.

In my opinion, the biggest determinant of your wealth from company stock is not going to be “did I exercise early or late?” It’s going to be if your company went public or not, which is utterly outside your control. Which could be a (perhaps strangely) freeing realization!

Try not to overcomplicate the decision. Know that “luck” is going to be a way bigger influence than anything else. And, in that spirit, good luck.

Do you want to work with a financial planner who can help you evaluate your biggest financial decisions from the perspective of what has the best chance of funding a meaningful life? Reach out and schedule a free consultation or send us an email.

Sign up for Flow’s twice-monthly blog email to stay on top of our blog posts and videos.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational, general information, and illustration purposes only. Nothing contained in the material constitutes tax advice, a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, or investment advisory services. We encourage you to consult a financial planner, accountant, and/or legal counsel for advice specific to your situation. Reproduction of this material is prohibited without written permission from Flow Financial Planning, LLC, and all rights are reserved. Read the full Disclaimer.