How are you feeling? After the chaos of the last few weeks and months in the markets, the economy, and national politics? After the last couple difficult years in the tech employment scene?

When things are going well in your life and career and the markets and the economy, you probably don’t think much about having “room for error” in your finances. Error, what error?!

Welp, I’m guessing so-called Recent Events have made “error” very obvious, and the idea of making room for it might sound pretty good, eh?

Three stories from my life in just the last two weeks have made me think about how valuable “room for error” is. [To give credit where credit is (probably) due, I think I got this specific phrase from the engaging, thought-provoking book The Psychology of Money.]

Story #1: Air travel

Last week, my family and I went to San Francisco for my girls’ Spring Break. Though we took Amtrak down (and try as they did, Amtrak couldn’t ruin the awesomeness of long-distance train travel), we flew back.

On that return flight, we arrived at SFO a full two hours before our flight.

We went directly to the TSA Precheck line in Terminal 1… where they told us we needed to go to TSA Precheck in Terminal 2. The whole thing probably added only about 20 minutes to the time it took to get to the gate and was ultimately pretty straightforward. That said, I tend to be a somewhat nervous traveler, especially when I have my kids with me, and uncertainty unnerves me.

Thankfully, that two hours—plus the fact that we’re all able-bodied, my kids are old enough to take care of themselves, we didn’t have bags to check, and we have TSA Precheck—was our “room for error.” Even with the addition of 20 minutes and some uncertainty about the new security process, I felt pretty unharried.

Story #2: The possibility of losing your job

While we were in San Francisco, we had dinner with a couple, both of whom work at a major hardware company. I’m no economist, but even I know that this company will be majorly impacted by tariffs.

I asked them how they were feeling about their jobs. The wife agreed that if tariffs were imposed for any meaningful length of time, the company would simply have to lay off a lot of workers, possibly her and her husband included.

I asked if, in anticipation of that very real possibility, they were trying to build a really big cash cushion. Turns out, they didn’t need to build one; they already had one. One that could last at least two years.

So, despite the fact that this couple had a pretty good chance of losing both their jobs in the current economic landscape (and being deposited into a nasty environment for finding a new job), they were fairly undisturbed by it. That cash cushion was a giant “room for error” that allowed them to still enjoy eating out with friends from out of town.

Story #3: Stock market gyrations

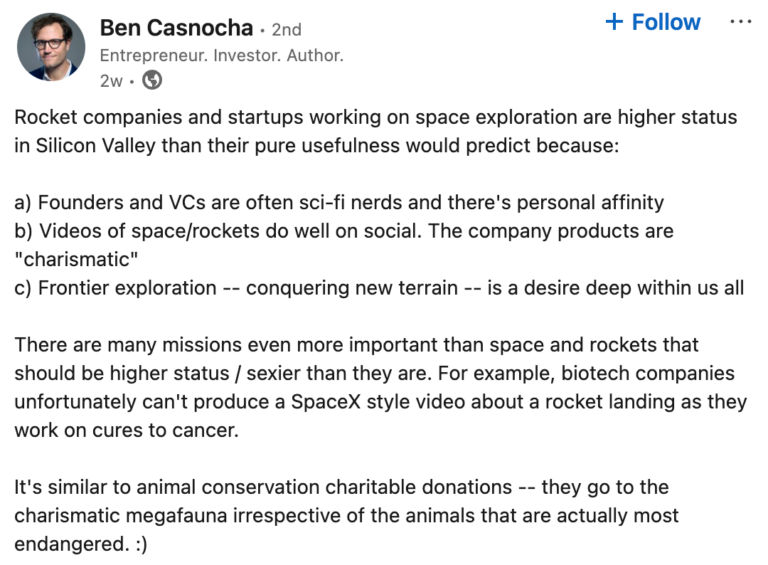

As you must know, the US stock market has been positively insane this year so far, and especially in the last couple weeks.

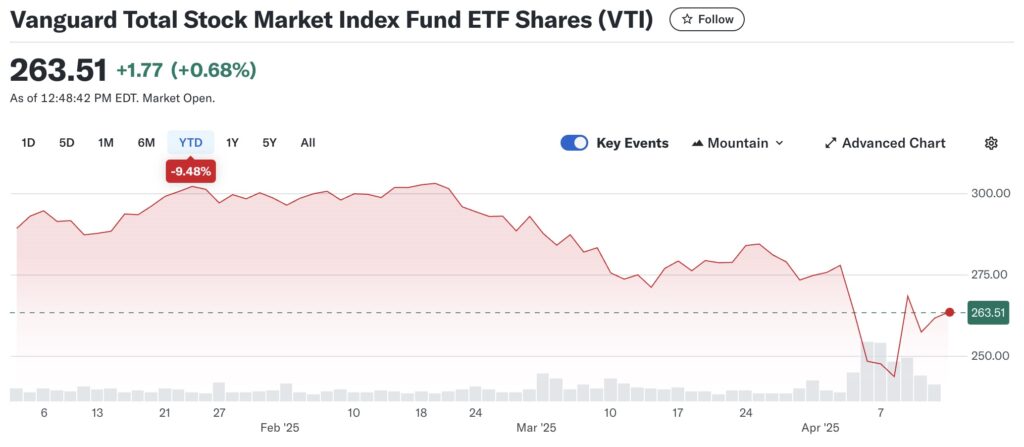

Here’s the US stock market year-to-date (as seen through the eyes of Vanguard’s Total US Stock Market ETF (VTI)). Just check out the last couple weeks, at the right of the chart!

Source: finance.yahoo.com April 14, 2025

It’s down “only” 9.48% as of April 14, having reached a nadir of 15% down just a few days ago. A lot of the big-tech company stocks are even worse off, down 15%+ after hitting a nadir of 20%+. And it’s going up and down wildly for the craziest of reasons, like maybe some dude whose last name is Bloomberg but not that Bloomberg posted something on Twitter/X about Trump calling off tariffs?

If you pay too much attention, you can start to get sea sick. If you need money from your investments now or soon, and you are invested in the stock market, this sort of craziness might make you feel a little nauseated.

But! Of my clients who don’t need their invested money for another 10+ years, I more or less haven’t heard a peep from them. (Now, let’s hope that’s because they’re not that worried, and not because they’re afraid to talk to me. I’m nice! I swear I am!) They have a lot of “room for error,” that is, they have a long time until they need to sell any of their investments to pay their expenses.

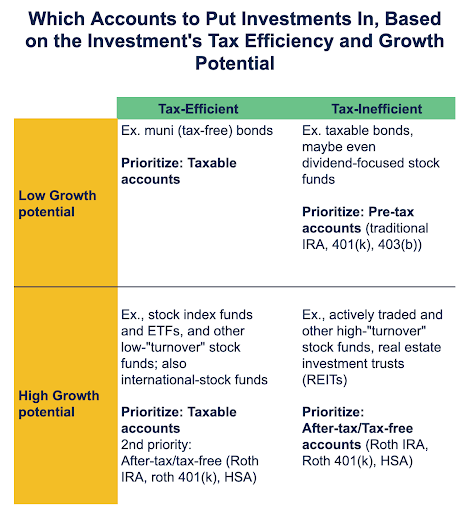

Of the clients who are living on their portfolios right now, I haven’t heard a peep from them either. Hopefully that’s at least in part because I’ve oft explained that when you have a diversified portfolio (very basically, both stocks and bonds), it’s kinda okay if stocks go down, because your bonds probably won’t. (Thus far, bonds—if you look at Vanguard’s Total Bond Market ETF (BND), which seeks to own the entire investment grade US bond market—are pretty neutral this year.) The bonds—which don’t tend to grow fast…but also don’t tend to lose value fast—are these clients’ “room for error.”

The few clients who are the most stressed out are the ones who have run through their cash cushion—or are close to doing so—and might need to start selling investments in a way they didn’t quite anticipate. They have depleted their room for error.

Your own “room for error”

How have you felt this last couple weeks, or this year so far? Have you been scared? Anxious? Thinking about making drastic changes in your life or finances? If so, you might need more room for error in your finances.

If you’re not yet in a pickle, then you have time to create room for error for your future self, who might find themselves in said pickle.

You could:

- Build a bigger emergency fund. Instead of setting aside enough cash to cover 3-6 months of spending, build one to cover one year (or more!) of living expenses.

- Save more for upcoming expenses than you think you’ll need. Saving for a remodel or a trip or a new car or a home purchase? You should, of course, do your best to estimate how much that thing will cost. But maybe then save, say, 25% more than that. You know and I know that things “have a way” of being more expensive than we think they’ll be. If you don’t use all that extra, great! You can deploy it, at that point, to other uses.

- If you are approaching retirement, consider buying some sort of annuity. Annuities are tremendously varied, some are very complex, and some are “sold, not bought.” But the simplest of annuities—give an insurance company a lump sum of money in exchange for them giving you a monthly paycheck for the rest of your life—can ensure you have a steady paycheck no matter what. the markets do. (I am personally a big fan of this kind of income annuity. Research shows that this sort of guaranteed income vastly increases the amount retirees spend, which is a good thing.)

- Ensure your living expenses are well under your current income. For example, if you have a salary + bonus + RSU income, live on your salary and save and invest your RSUs and bonus. In my world, as a business owner, with two types of income, I have a similar dynamic: I live on my salary and save and invest profit distributions from the business.

Intentionally not optimizing

In my view, creating “room for error” is in opposition to optimizing.

A full year of expenses in cash? My goodness, I could be investing some of that money! And, the stock market goes up 74% of the time, so I would be better off in the long run!

(I got that percentage from this article, which says that “Since 1980, the S&P 500 has been positive in 32 of 43 years.”)

Buy an annuity? Good grief, I could keep all that money invested and, statistically speaking, will end up with way more money upon my death!

Live just on my salary? But I could be living so much “larger” instead!

I am not persuaded of the merits of optimizing. It usually takes way more effort to optimize than it does to get to “good enough,” and the pursuit of optimization gets you closer to the edge of “Sh*t’s gonna break if something goes awry.” In general, it can create a lot of stress.

One of the roles of money in my life is to reduce stress so I can enjoy the rest of my life.

In good times, optimizing might seem the obvious approach. But when times turn bad, I think you’ll thank yourself for having built in more room for error instead.

Do you want someone to help you figure out how much financial room for error is right for you?