Do you have a charitable spirit? Maybe you already give some money away. Perhaps you want to start giving. Are you stymied by the “But HOW exactly?” of charitable giving? Is it hard to figure out how much money to give and which organizations to give the money to?

We might have a sense that Super Rich People have very detailed charitable giving plans (and many do), but how do more or less Normal Schmucks Like Us bring similar intention to our charitable giving?

There is no one way. In fact, about a year ago, I wrote a post entitled “Just pick an easy way to give to charity and go.” And that’s still my overarching attitude. I mean, even if I had had a structured charitable giving plan for 2020, it flew out the window as soon as March hit. The need was just too vast, too overwhelming, to be thinking about percentages or schedules. (To be clear: I say this from a position of personal financial strength.)

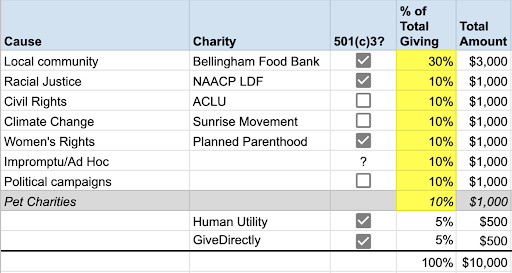

But having a plan, giving with intention is good. So, to support that, I offer up the process by which I am making my charitable giving plan going forward. Here’s the spreadsheet I am using. Maybe it’ll be useful as a starting point for you, and it will make it easier for you to create your plan and start giving more intentionally.

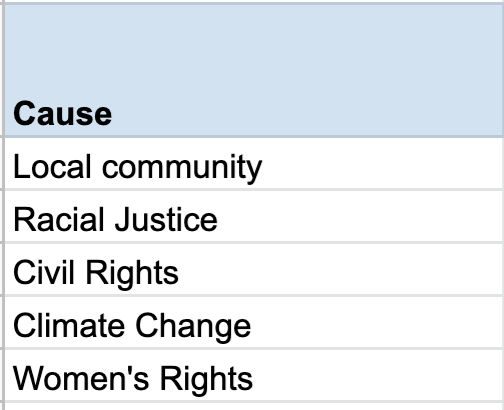

Step 1. As Always, What Do I Care About?

What causes or communities do I care most about?

For me, for now, and in no particular order, it’s:

(Yes, I’m just copying from the spreadsheet I linked to above.)

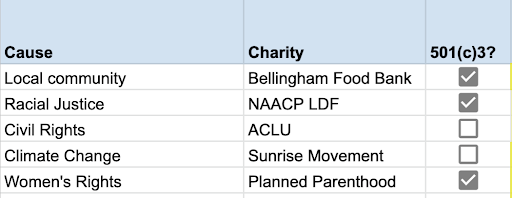

Step 2. Which Organizations Do I Think Can Best Support Those Causes?

Now it’s time to choose organizations that can best serve the causes I care about. Or, if “best” is too high a bar, which organizations can support them at all?

There are many many people out there who know more about the internal workings of charities than I do. I know that some of my money is going to be wasted. What I don’t know is how to eliminate or minimize that, beyond checking well-known sites like Charity Navigator (which I do).

For me, it’s important to choose organizations that address problems from “both ends,” which is to say, I want to support organizations that work:

- Proactively, trying to change how “the system” works to avoid bad stuff in the future, and

- Reactively, trying to make things better for people, communities, land, animals, etc. in need Right Now

I remember reading some time ago that the United States is pretty unparalleled in their rescue efforts, especially internationally, when Bad Stuff happens. Hurricane in Haiti? We’ll drop soldiers and doctors and food and infrastructure from the sky as if we’re gods. But we are at best neutral when it comes to helping set up infrastructure, policy, etc. ahead of time so the herculean rescue efforts won’t actually be necessary in the first place.

I get that playing Hero feels great. And it’s necessary. So, I want to give to reactive organizations.

But in the long run, I know that proactive, preventative efforts have the bigger potential to minimize or prevent suffering.

So, here’s the next iteration of my plan:

I know there are so many more organizations that support these causes. Some might be better. I intentionally limited my Googling/research time and sometimes just “went with my gut.” My biggest fear is analysis paralysis, not a sub-optimal charity choice.

I also include some other causes and organizations to give myself a little bit of flexibility.

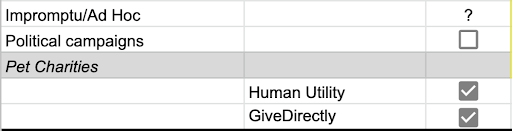

Step 3. How Much Money Should I Give?

I’m going with the tried and true 10% of income. I’m not religious, but hell, it’s the closest thing we’ve got to a god-given directive around charitable giving, and who am I to mess with that? Really, it’s just an arbitrary but reasonable line in the sand. Again, avoid the analysis paralysis.

If 10% sounds daunting to you, let me reiterate two things:

- I’m coming from a place of personal financial strength. I will not endanger myself financially by doing this.

- Start anywhere. Just give.

And, in case you want to get picky, what do I mean by “income”? I decided to use my Adjusted Gross Income. Why? I—or rather, my CPA—calculates this every year around March for my taxes. It’s a number that is calculated in the same way, every year, providing consistency and requiring no extra work.

Which means that some time in March or April this year (and every year hereafter), I will sit down and finish my charitable giving plan for 2021.

Now, if you’re detail oriented, you might say “But Meg, you only know this year’s AGI next year when you do your taxes! So, you’re not matching up the year of income with the year of donations!”

And you’re right. Ideally, in big income years, I’d want to make the big charitable donations (for the big tax write-offs) in the same year.

The way I’m doing it, I could make $500,000 in 2021 (these are not real numbers) and therefore commit to donating $50,000 in 2022. But what if my income in 2022 is only $100,000? That’s not good.

Here’s why I’m okay doing it this way:

- I expect my income to in fact only go up, as I continue to grow my business. Even if it doesn’t, it shouldn’t be anywhere near volatile enough to have that $500k/$100k problem. (If you have a particularly big income year—IPO, a ton of valuable RSUs vested, etc.—you can tweak your strategy in order to give more in the year that you incur your income. Say, in November, look back at what income you’re on track to earn that year and give away a rough 10% of it by year’s end.)

- I might optimize for the timing of donations in future iterations. Right now, it seems too hard and I’m more concerned with making it simple enough to Get Going.

So, let’s say my AGI for 2020 = $100,000 (easy math).

And then I not-remotely-scientifically assigned a percentage of that $10,000 to each of the charities I’ve selected, and my nifty spreadsheet calculates the dollar amount.

Step 4. Can I Give Them Appreciated Stock Instead of Cash?

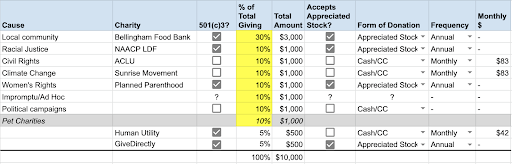

The one real nod to tax optimization I do in my charitable giving is to give appreciated stock instead of cash when it’s permitted and easy enough (for me and the charity).

But I figure this out only after I’ve figured out which organizations I want to support.

If I can donate appreciated stock, I will. And because it’s administratively heavy, I’m going to do it just once a year. If I donate cash, it’ll be a monthly, recurring credit card contribution, because it’s easy, set it and forget it.

[Note: I know that charities prefer getting a recurring, predictable monthly contribution over a one-time lump sum contribution. So here I am prioritizing my own financial benefit over the ease of the charity. Ultimately, you could argue that because I’m getting a nice tax benefit, that I might end up giving more to charity. But right now, I’m simply making a selfish choice.]

So, now I have a fully fledged strategy:

Step 5. Actually Give Away the Money.

For the charities that I’m going to give cash to, it’s easy peasy. Go to the charity’s website right now, give them my credit card number, the monthly $ amount, choose “monthly,” and click Submit. Done! I don’t have to think about this again until next year, when I might change charities or the amount of money I’m giving.

Donating Stock Takes More Effort

For donating appreciated stock, it’s more work. As such, I recommend:

- Don’t do it for less than, say, $1000 probably. (I realize my chart shows I’d give $500 in appreciated stock to GiveDirectly. If these were really my numbers, I’d likely give cash to GiveDirectly.)

- Do it just once a year for each charity

At our firm, we frequently help our clients fill out the paperwork from their custodian. We manage our clients’ investment portfolio at TD Ameritrade and can easily help from there. Sometimes, however, we’re instead helping them give company stock from their company’s stock plan account at, say, Morgan Stanley.

For me, I will pick a time of the year when I do all these donations. Put it in my calendar. Make it before December so it’s not last-minute stress. Charities are happy to receive money at any time, and it doesn’t matter from a tax perspective when I give the money within a single year. People usually donate near the end of the year, but the only real reason to do that, I think, is so I’ll have a better idea of what my income and financial situation will be like that year.

I need to find that gifting/donating paperwork at my custodian (Schwab, Morgan Stanley, TD Ameritrade, Vanguard, etc. Alas, last I checked, you couldn’t donate investments directly from your Robinhood account. You’ll have to transfer the investments to a place like TD Ameritrade first. Which, yes, we’ve helped clients do, because…Robinhood…I was irritated with them before it was cool!).

On that paperwork, I have to identify:

- which appreciated stock to give away (investments that have a large percentage gain, and also investments that I might not want to keep because they’re not appropriate investments for me)

- How many shares to give away. If the stock is worth $10 now, and I want to give $1000, then I give away 100 shares.

- If I’m not giving away all of that stock, which “tax lots” of the stock to give away (the lots with the highest percentage gain)

- Details about the receiving charity. You can often find this on the charity’s website, or you can call/email them and ask for it. Usually, it’s:

- DTC #

- where their investment account lives (Morgan Stanley? Schwab?)

- the account #

- the name on the account

Honestly, I don’t want to describe this any further. If you’re not familiar with the idea of tax lots and cost basis, this can get confusing (if it hasn’t already…and perhaps it’s just my inadequacy in explaining!). But if you’re going to give away appreciated stock (or funds), you will need to familiarize yourself with these ideas to optimize this tax tactic.

And then I’m sure to follow up with the charity to ensure that they receive the donation, they know it’s from me, and they issue me a tax receipt indicating the value of the stock when they received it. That is the value I get to write off in my taxes. This can get messy with charities that don’t have a good process in place for this sort of donation.

Step 6. Forget About It Until Next Year.

Now, of course, if you had set up a giving plan in January 2020, you’d be forgiven for throwing it out and just giving out money willy nilly. But in general, I’d say, one of the big benefits of creating and following a giving plan is that you can now get it—the analysis, the anxiety, the guilt—out of your head.

And if I know one thing about working with so many people on their finances, it’s that a desire to get rid of the ever-present anxiety, shame, guilt, and all sorts of other yucky, persistent, background emotions can be the primary driver for actually working on your finances.

Notice What I’m Not Doing

I’m not using a Donor Advised Fund.

I’m not “bunching my donations” in one year.

I’m not matching up the year of (big) donation with the year of (high) income.

I am not giving only to causes that give me a tax write-off.

In general, I’m not optimizing for taxes except that I give appreciated stock when the organization permits it.

In future years, I might iterate on this plan to include some of that tax optimization. But this is my first year of really structured charitable giving, so I’m going for a Minimum Viable Product here.

I hope that seeing the process by which I built my charitable giving plan, and having the spreadsheet itself will help you get off your duff and start honoring your charitable intentions more fully this year.

Do you want to work with a financial planner who wants to encourage your charitable spirit, and can help set up straightforward and actionable steps to give? Reach out and schedule a free consultation or send us an email.

Sign up for Flow’s weekly-ish blog email to stay on top of our blog posts and videos.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational, general information, and illustration purposes only. Nothing contained in the material constitutes tax advice, a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, or investment advisory services. We encourage you to consult a financial planner, accountant, and/or legal counsel for advice specific to your situation. Reproduction of this material is prohibited without written permission from Flow Financial Planning, LLC, and all rights are reserved. Read the full Disclaimer.