Do you know, more or less, how RSUs work, but ESPPs are a complete mystery? Join many of our clients in that confusion. And frankly they are stupidly complicated for the amount of money they’re worth to you.

And while Employee Stock Purchase Plans are fairly common in big public tech companies, they’re not nearly as common as RSUs. Google and Amazon, for example, have RSUs but not ESPPs.

[Note: This article was originally written in 2016. I went to send it to a client and was hahrified, HAHRIFIED, by what I found. So I almost entirely rewrote it. You ever read something that you wrote 7 years ago? Yeah…]

As it turns out, ESPPs can be Free Money. Well, there’s some risk, and my compliance consultant is probably having an aneurysm over the use of that phrase, but often you can keep the risk really low and come out…maybe a few thousand dollars ahead.

I hope this article helps you understand how they work…and also how you probably shouldn’t get too excited over them.

[Note: This article is about qualified Employee Stock Purchase Plans (as opposed to non-qualified). The qualified kind is most likely what you’ll receive as an employee of a tech company.]

How Does an ESPP Work?

I can easily explain at a very high level how it works:

An ESPP allows you to buy company stock at a discount (up to 15%) off the stock price.

First, Some Terms You Have to Understand

Anything more detailed than that, you’re gonna have to endure some vocabulary lessons first:

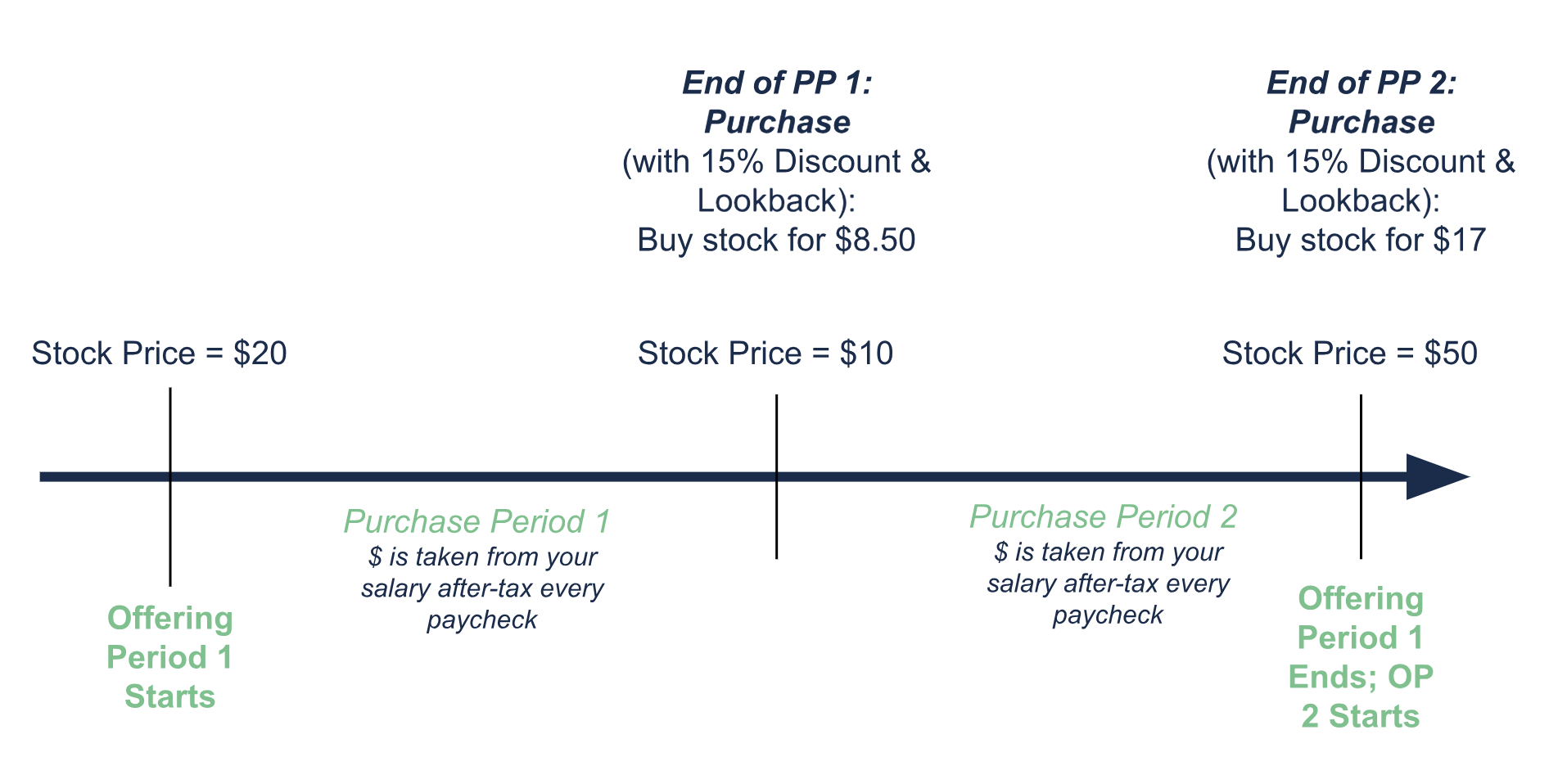

- Offering Period: This is usually one to two years long. The most important thing for you, the employee, that comes out of the Offering Period is the price of the stock at the beginning of the Offering Period. This shall come up later!

- Purchase Period: There are usually multiple Purchase Periods within an Offering Period. A common setup is to have a one-year Offering Period, with two 6-month Purchase Periods within it. Or a two-year Offering Period, with, you guessed it, 4 6-month Purchase Periods within it.

Your participation in the ESPP is taken Purchase Period by Purchase Period. Even if the Offering Period is two years long, you can choose to participate in only one Purchase Period.

- Lookback: With a lookback, that (15%?) discount is calculated off the lower of two prices: the stock price at the beginning of the Offering Period, and the stock price at the end of the current Purchase Period). If your company stock has gained a lot of value since the beginning of the Offering Period, you can perhaps see how nice this would be!

Lookbacks are good! And quite common in Big Tech. Without a lookback, the discount is taken off the price at the end of the current Purchase Period. This is just fine, but it’s never going to give you a chance to make a lot of money.

Airbnb’s ESPP is the best example I have:

- It listed at $68 when it IPOed. Its ESPP Offering Period started that day, offering the highest discount (15%) and a lookback.

- When its first Purchase Period ended 6 months later, the price was closer to $150.

- Airbnb employees participating in the ESPP got to buy ABNB stock at 15% off $68 = $57.80!

- In conclusion: Whoa.

Now, the Actual Process

- Choose the percentage of your salary to deduct from your paycheck. This is set anew for each Purchase Period.

- Your company caps the percentage you can contribute; a common limit is 10%.

- You can, in fact, only buy $25,000 worth of company stock each year (that $25,000 is calculated based on the stock price at the beginning of the Offering Period). Typically, that means you’re quite limited in how much you can buy.

- That money is withheld from each paycheck for the entire Purchase Period.

- To give you a sense of scale, if you max out your participation in the ESPP over the course of a year, you’re going to have about $1770 less coming home to you per month in your paycheck. (That’s $25,000 minus the usual 15% discount, divided by 12 months.)

- This money is after tax money. You don’t get a tax benefit by setting it aside, as you would for contributing to a pre-tax 401(k).

- It gets kept as cash for that entire Purchase Period and is not at risk.

- If at any point during the Purchase Period, you need that cash, you can ask for it back. You can get it back…but if you do, you can’t reenroll in the ESPP until the next Offering Period starts. It’s a nice failsafe, though.

- Company stock is purchased with that accumulated money at the end of the Purchase Period.

- The stock is purchased at the discount to the stock price.

- If your plan has no lookback, that discount is applied to the price now. If there is a lookback, then you use the lower price of now or earlier (as explained above).

- You now own some shares of your company’s stock in a taxable brokerage account of your employer’s choice (Fidelity, Schwab, etc.).

- This is the same account that your RSU shares would also show up in when your RSUs vest (if you also get RSUs).

Should You Participate?

Probably.

Keep in mind that some ESPPs suck. My husband had an ESPP at HP many years ago. They offered a 5% discount. I remember calculating that we could earn $400 after-tax over an entire year of participation. I decided it wasn’t worth the hassle.

Is there a small discount? Is there no lookback? My opinion of your participation is more along the lines of “meh.”

But if you have a 15% and a lookback? Those are some reeeeeal nice terms…

Estimate How Much Money You Can Get From Participating

Before you decide to or not, you need to know:

- Discount

- Whether there’s a lookback

- Max amount you can contribute

Then run (or rather, approximate) the numbers for your company’s ESPP:

- Multiply $25,000 by the discount, let’s say 10% = $2500.

- This is the amount of pre-tax income you’ll receive, assuming you don’t have a lookback. If you have a lookback, then you really can’t know how much this will be worth to you.

- Estimate your total federal and state tax rate, let’s say 35% federal + 9% state + 0.9% Medicare = 44.9%.

- Subtract that tax amount off your pre-tax income from the ESPP: $2500 – 44.9% = $1377.

- This is the amount of money you’ll actually usefully make from the ESPP.

Any time you’re dealing with stock compensation, you need to think along three lines:

- Taxes

- Your investment portfolio

- General planning

Know How It Impacts Your Taxes.

When the stock is purchased for you at the end of the Purchase Period, you don’t owe any taxes. The taxes come into play when you sell the stock.

As you will begin to see below, the tax treatment of ESPPs can get pretty hairy, “qualifying disposition” and “disqualifying disposition” and all that. I paint only a general picture of things here, with the goal of not hurting your brain…to much. If you’re going to actually participate in an ESPP, you’ll benefit from some Detailed Tax Analysis. Work with a tax professional!

If you sell as soon as possible after acquisition (sometimes there’s a few-day wait before the trading window opens): You will pay ordinary income tax—the same tax rate you pay on your salary—on the discounted amount and likely little else in tax because the stock won’t change much in price.

If you sell within a year after acquisition or within two years after the start of the relevant Offering Period): You should pay the same ordinary income tax on the discount amount, but in addition you pay short-term capital gains taxes on any subsequent gains.

If you wait at least one year after acquisition and two years after the start of the relevant Offering Period to sell: Again, you will pay ordinary income tax on the discount amount. What is the discount amount? Ah yes, you’ve hit upon one of the (many) confusing bits: The discount amount is calculated on the share price as if the purchase occurred at the start of the Offering Period (i.e., based on the share price on the day the Offering Period started), not on the actual purchase date. This is the case whether or not there’s a lookback!

This time you pay long-term capital gains taxes on any subsequent gains (if want to get technical—which of course we cannot avoid with ESPPs—the tax is on gains above your cost basis (purchase price + taxable income recognized)). If the stock has fallen in value since you acquired it, it’s possible you will not owe any tax at all.

Long-term capital gains tax rates are lower than short-term capital gains tax rates, which are the same as ordinary income tax rates. It gets more complicated from there, and this isn’t a tax blog post, so I’ll leave you with “Use a CPA who knows equity comp.”

If you really want to see a numbers-heavy example of how taxes on an ESPP might work, check out what TurboTax has to say about it. Or even myStockOptions.com, a platform dedicated exclusively to equity compensation: a FAQ and an article with videos. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Don’t Let Company Stock Dominate Your Portfolio.

Or at least, be very aware if you are, and what the risks are of doing that.

The question now is: How much of the company stock should I hold?

It’s easy to build up a large holding if you’ve worked for the same company for years and you’ve been regularly acquiring stock this way and that (usually through RSU vests and ESPP purchases).

Although I usually prefer to hold no individual stock, you could probably persuade me that 5% of your investment portfolio is a reasonable upper limit. Especially if your persuasion strategy involves Rechuitti truffles.

The safest way to maximize your value from the ESPP is:

Contribute as much as you can to the ESPP, and sell all the stock as soon as possible after receiving it.

Just as you want a diversified portfolio, you want a diversified financial picture, too. It increases your total financial risk to have both your investments and your job with the same company. Certainly 2022 and 2023 have shown us painfully just how bad employment and stock value can get in the tech industry. Yowch.

Know How It’ll Affect Your Cash Flow and Savings.

I think ESPPs are, to first order, a cash-flow challenge.

ESPPs are enforced savings.

ESPPs usually don’t provide much in the way of extra after-tax dollars. If you buy $25,000 worth of stock at a 15% discount, that’s $3750 of “free money,” which is then subject to ordinary income taxes of let’s say 45% federal + state, leaving you with $2062 of after-tax money.

But! what you actually get at the end of a 6 month purchase period is not just that “free money.” It’s all the stock you purchased, which is worth a lot more. Now, most of that value is probably your cash that went into buying that stock, but hear me out:

This is enforced savings. Kind of like paying too much on your taxes and getting a tax refund!

And, for the record, I luuuurve those kinds of behavioral hacks.

What will you do with the extra money at the end of the Purchase Period?

What will you do with the money at the end of the Purchase Periods? (Let’s assume you sell the shares.)

Are you saving up a house downpayment, or for your kid’s college?

Do you have a debt you’d really like to pay off, like a mortgage or student loan?

This could be an opportunity to make some gratifying, instant financial progress.

You Have to Live on Less Income 6 Months at a Time.

When you participate in the ESPP, your paycheck is going to be lower than you’re accustomed to, because the employer is withholding money for the eventual stock purchase. Can you survive on that smaller paycheck?

If not, what will you use to pay your bills? Do you already have a stash of cash you can deplete? Or can you use your RSU income (or the proceeds from the previous Purchase Period’s ESPP sales) to pay your bills now?

Miscellaneous but Potentially Useful Bits about ESPPs

- You know how it’s all tax optimize-y to donate appreciated shares of stock instead of cash to charity? (Now you do.) ESPP shares are not good examples of this, because of the built-in bit of ordinary income from that “discount” money. Donate something else.

- Let’s say you leave your job with the ESPP. You have shares from both RSUs and the ESPP. You want to transfer those shares to another brokerage account somewhere else. Most likely you’ll be able to transfer the shares from RSUs but not from the ESPP.

Why? Because when you eventually sell the ESPP shares, even if you no longer work at the company, you’ll owe ordinary income tax on the discount amount, and that ordinary income will run through your company’s payroll department. Which means they need to keep track of it.

So, there we go.

Most of the time, ESPPs are “Yeah, sure, go ahead and participate. Just sell the stock immediately to reduce your investment risk. Make sure you know how you’re going to pay your bills while your paycheck is decreased for the next 6 months. And let’s make a plan for the money you’re gonna have once you sell.”

Sometimes they’re “Lord, this isn’t worth the effort.”

And rarely they pay off big time, usually in the event of an ESPP that starts at IPO date, and the IPO goes really well. But really, it’s whenever there’s a lookback and the stock price rises a lot during the Purchase Period.

Go forth and “meh”!

Are you wondering if or how you should participate in your company’s Employee Stock Purchase Plan? Are you trying to figure out how to make it work with the rest of your finances? Reach out and schedule a free consultation or send us an email.

Sign up for Flow’s twice-monthly blog email to stay on top of our blog posts and videos.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational, general information, and illustration purposes only. Nothing contained in the material constitutes tax advice, a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, or investment advisory services. We encourage you to consult a financial planner, accountant, and/or legal counsel for advice specific to your situation. Reproduction of this material is prohibited without written permission from Flow Financial Planning, LLC, and all rights are reserved. Read the full Disclaimer.