If you’re moving from a giant, public tech company to a pre-IPO company, especially a small pre-IPO company, you’re in for some meaningful changes.

The changes will be both financial and cultural. You, being in tech and having friends and colleagues across many tech companies, likely know way more than I do about the cultural stuff, so let me focus on the financial.

I want to look through two lenses:

- Private, as opposed to public. The biggest impact here is whether your equity comp is real money or fantasy money.

- Small, as opposed to large. Private companies can be big (think Airbnb before it went public) and small (think your classic startup). Size can influence the type of equity you get and also the robustness of your employee benefits.

You know instantly, if you think about it, that moving from Google (really big, public) to Stripe (really big, private) is very different from moving from Google to, say, Onward (“expense tracking for modern co-parents,” which has recently raised a Series A, I believe).

If you’re making the move from public to private, I hope this post helps prepare you for the changes—mental and/or logistical—you’ll likely have to make.

Your Salary Is Your Total Compensation. Your Equity Comp Is a Hope and a Dream.

If you work in a public company, your total compensation is your salary plus perhaps an even larger dollar value of Restricted Stock Units (at least, prior to this dumpster fire of a year).

In a private company, you might still receive salary plus company equity. But do you want to guess how much your total compensation is, in practical terms? Your salary and only your salary. (Okay, maybe a bonus, but I’m simplifying here.)

Private-company equity compensation is “future fantasy money,” as a client once dubbed it. It’s not now, real money. And you should behave accordingly.

In a public company: Your total compensation = Salary + company stock you can actually buy bananas with

Vs

In a private company: Your total compensation = Salary + Lottery ticket

Don’t let the “promise” of big equity value hold undue sway in your decision about which job to take. We’ve had plenty of clients, especially at smaller startups, who left their company with zero equity value because the company had gone out of business or simply failed to make any progress. It’d be a shame to sacrifice a job that actually intrigued you (or take one you didn’t want) for the sake of equity comp that came to naught.

Adjust Your Lifestyle to this Lower Total Comp.

You have to be able to make your financial situation work with only your salary, because that’s the only money you can rely on (to the extent you can rely on anything as an employee in tech…I see you, you laid-off workers!).

Do not incur any expenses that depend on that equity being worth anything. Because it might never be. Don’t buy a home bigger than what your salary can support. Ditto with a car.

If you’re accustomed to living on salary + public-company RSU income, this can be hard, because you’re changing long-ingrained habits. Changing habits is the worst.

You’ll need to look at your expenses for the things you feel you cannot live without, and see if the private-company’s salary covers it. If it doesn’t, then you need a higher salary (or to lower your expenses).

Decisions about Your Equity Compensation Are Different and Often Harder.

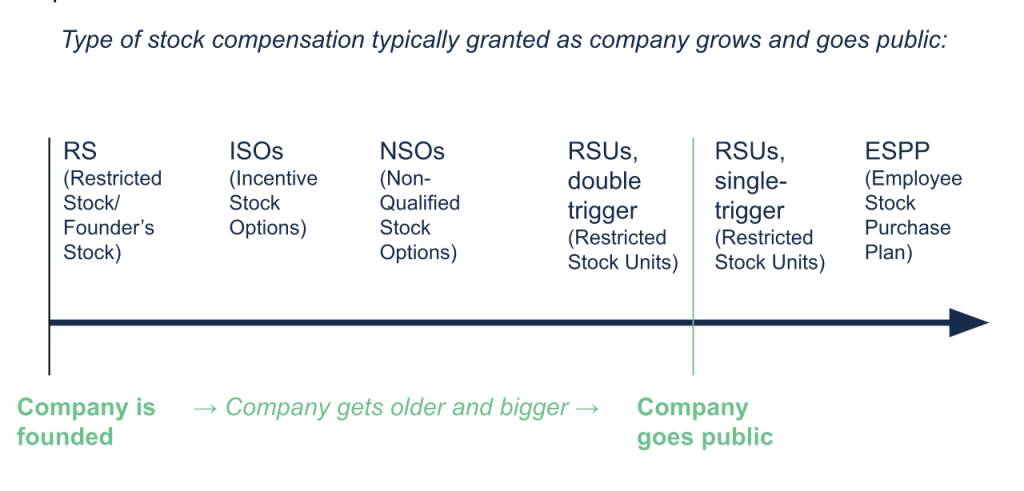

Here’s the rough timeline of when in a company’s growth you get what kind of equity compensation:

Equity Decisions at Public Companies

At public companies, you usually only get RSUs and ESPPs.

You have two decision with RSUs:

- Hold or sell after they vest

- In some companies: whether or not to withhold more tax upon vest than the statutory 22%

You have two decisions with ESPPs:

- Participate or not (you likely should because it can be close to “free money”)

- Hold or sell after the purchase

Equity Decisions at Private Companies

At earlier-stage private companies, you usually get options: Incentive Stock Options at younger companies, and Non-Qualified Stock Options at slightly older companies.

At later-stage private companies, you start to get Restricted Stock Units.

Stock Options

If you have options—be they ISOs or NSOs—you have 2 1/2 decisions:

- When to exercise

- How many to exercise

- After exercising, when to sell (that is, if you can while the company is still private)

All of these can have big financial impacts.

If you start at an early-stage private company (seed round, Series A), before their stock is worth much, then the cost of exercising options—exercise price + taxes—can be low.

By contrast, if you join a later-stage company with a higher valuation, or stay at an earlier-stage company long enough that it becomes later-stage, then the cost of exercising options is much more expensive.

It’s all relative to your financial situation, but if exercising will cost you $500 in the first scenario, that’s a less fraught decision. But if it’s $100,000 in the second scenario, then that’s a decision you don’t want to screw up.

Let’s say you do exercise, and now you own shares in the company. Do you hold them and wait for an IPO? Do you try to sell them via a private secondary market?

RSUs

Once companies get gigantic, but still private (think Airbnb in the two years before its IPO), you’ll likely get only RSUs.

Most big private tech companies I have experience with issue “double-trigger” RSUs, which you don’t have any say over until the company goes public. So, no decisions there.

It’s possible you’d join a private company that issues single-trigger RSUs. If they’re single-trigger, that means the RSUs will actually fully vest while the company is still private, and when they vest, you’ll owe income tax on the value of the stock. Of course, you usually can’t sell the stock in order to pay the tax bill. Which is the problem.

So, the big decision for single-trigger RSUs is: Do I pay taxes by having more shares withheld upon vest, or do I pay some of the tax bill out of pocket?

A Minor Consideration: There Are No ESPPs at Private Companies.

Losing access to an ESPP is rarely, in my experience, something anyone pays any attention to. For all the anxiety and confusion and print and time given to them, ESPPs generally just aren’t worth that much money. They will generally get you a low number of thousands of dollars, before you pay taxes on them. So, don’t waste too much thought on them. (They can be more valuable in recently, successfully IPOed companies.)

Employee Benefits Depend More on Company Size than on Public vs. Private.

I don’t have any sort of training in HR, so this is purely from observation of our clients, but the benefits packages we see our clients get depend much more on the size of the company than whether the company is public or private.

I am not including equity compensation in this discussion. I am talking about things like health insurance, 401(k) plans, and other, ancillary employee benefits.

Airbnb in its last two years of private-ness offered benefits a lot closer to Google’s (public, but large) than it did to what, say, an Onward (private, but very small) would offer.

For example, big tech companies:

- often offer after-tax 401(k) contributions, regardless of whether the company is public or private.

- often cover most—and sometimes all—of the premium for health insurance coverage for its employees, whether the company is public or private.

- sometimes allow its employees to pay for their long-term disability insurance with their own money.

[Random financial planning fact alert! Paying for your long-term disability insurance from work with your own, after-tax dollars is often a good thing. Why? If you pay the premium with your after-tax dollars, then if you ever become disabled and claim benefits, those benefits will be tax-free. Whereas if your company pays the premium, those benefits would be subject to income tax.]

By contrast, we’ve seen earlier-stage startups not even offer what I consider pretty basic employee benefits, like long-term disability insurance.

So, if you’re moving to a private company, pay attention if you’re moving to an early-stage company, as you might be losing out on some big benefits.

If Things Go Well, You’ll Be Dealing with Gigantic Shocks to your Financial System.

If you have worked at Google or Amazon over the last five years, you know you can build wealth at a pretty fast clip, because those RSUs have been worth a lot of money.

So, building wealth at a public company is very possible, and you can do it fairly quickly—and steadily—over time: RSUs vest each quarter, and you ideally sell the RSUs and sock away most of that money.

Building wealth in a private company is different.

As discussed above, the salary should be enough for you to:

- Pay your current bills

- Build an emergency fund, and

- Save enough for your long-term financial independence so that you’ll be able to retire at a reasonable age, even if you never have any sort of lucky windfall.

Because your equity compensation isn’t worth anything now, you likely don’t have the ability to save a ton of money, as you would at a public company where the equity compensation regularly drops large chunks of cash into your lap.

You are, of course, hoping and praying and waiting for an IPO, a tender offer, an acquisition, or a direct listing to turn your equity compensation into lots of money in one fell swoop.

If it happens, and happens well (enough), then you’re going to go from a steady drip of a “pretty good income” to “Yikes, this is a lot of money…and all at once.”

Which is to say:

If things go well, your financial experience will be a lot more volatile in a private company.

It can be much easier to design your life around a steadier financial situation, which you could have if you worked at a public company with regularly vesting equity compensation. (This is not to say that RSU income in a public company is steady. The last year has shown us just how much it can change. It is, however, steadier than salary salary salary salary Big IPO!)

If your private company goes public, and you have meaningful equity in it, then the lifestyle and/or financial structures you have designed for your pre-IPO existence suddenly don’t make sense anymore.

Your sense of your own wealthiness suddenly no longer matches your financial reality. We saw this a lot in our clients who went through the Airbnb IPO.

One day, “I’m a two-hundred-thousand-aire!” The next day, “I’m a two-million-aire!”

The financial circumstances changed dramatically literally overnight. You can now afford to pay for, say, first-class plane tickets or to take a long sabbatical from work.

Your identity, your relationship to money,…none of that stuff can change overnight. You can’t imagine paying for first class or stopping earning a paycheck.

So, there’s instantly a tension between your financial reality and your financial perception. It can take months and years for those two to converge.

The Shadow Side: If You Play it “Wrong,” Those Financial Shocks Could Be Destructive.

The scenario above is, mmmm, mostly good. “Mmmm, mostly” because getting a bunch of money isn’t all good. It can be disruptive to your life and happiness and stress level.

But

- if you work at a private company that gives you stock options, and

- if the options are expensive to exercise (which generally happens in a later stage, successful private company), and

- if you exercise them anyways, paying both the exercise price and the associated tax bill (don’t forget the tax bill!)…and

- then the stock price goes down

You can lose a lot of money.

Maybe you’ve heard about the ability to finance the exercise of options, i.e., risk someone else’s money, like ESO Fund or EquityZen or Vested. Even if you do that, you can still lose meaningful money. If your stock loses value and the loan to you is forgiven, that forgiven loan amount is treated as taxable income to you! So, maybe now you own taxes on a $200k loan! You got an extra $50k lying about to pay to the IRS?

Which is all to say, you can—and many fine, smart people do—really f*ck this up if you’re unreasonably optimistic and/or don’t fully understand how taxes work or financing works.

If you’re making the move from a big public tech company to a private company, especially at an earlier stage, some things are gonna be way different. Just go in eyes open!

If you like the idea of having someone help you think through the broader implications of all these big life decisions, reach out and schedule a free consultation or send us an email.

Sign up for Flow’s weekly-ish blog email to stay on top of our blog posts and videos.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational, general information, and illustration purposes only. Nothing contained in the material constitutes tax advice, a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, or investment advisory services. We encourage you to consult a financial planner, accountant, and/or legal counsel for advice specific to your situation. Reproduction of this material is prohibited without written permission from Flow Financial Planning, LLC, and all rights are reserved. Read the full Disclaimer.