If there’s one topic that our clients have no idea how to figure out, it’s the question of when to exercise their stock options. (Also, “What do you mean, the tax code works like that?”)

Stock options supposedly are your ticket to riches…but how do you actually do that? How do you decide when to exercise them and sell them and turn them into grocery money?

In this article about what to do with your options if you worked for Airbnb prior to IPO, I introduce the idea of leverage. Leverage is what makes options so durn valuable, and potentially much more valuable than other forms of equity compensation, like Restricted Stock Units.

Leverage is something I have struggled to explain to clients in an easy, intuitive way because, well, it wasn’t intuitive to me.

But comparing it to a home mortgage is what helped me understand it more intuitively, helps me explain it to my clients in a way that I hope is easier to grasp, and now I shall practice on you.

Wish me luck!

We’re talking only about NSOs at public companies.

I am talking exclusively about non-qualified stock options (NSOs) in public companies—including recently public—but not private companies. And not ISOs. The considerations are just too different for me to effectively address both simultaneously.

Maybe your public company granted you NSOs (like Netflix and Spotify do in their weird-ass equity compensation plans). Or maybe you had options in a private company, and that company went public—by IPO, direct listing, or by being acquired by another company—and now, like magic, you have options in a public company.

It’s all the same! Except that in the case of your private company going public, you’ll likely have a way lower exercise price than the likes of Netflix and Spotify or other public companies that grant you options. Why? Because companies have to grant options with the exercise price set to the current stock price, which is way lower in private companies, especially earlier stage private companies.

Leverage when buying a home: Your mortgage!

When you buy a home, typically you get a mortgage, right? Either you don’t have the full purchase price in cash, or you don’t want to put all your cash into your home.

Buying a home by borrowing part of its purchase price is what gives you leverage. The mortgage is the leverage.

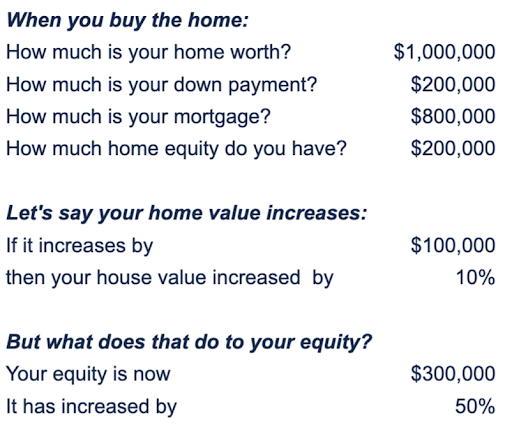

In an “up” market, it works wonderfully! Behold…

Whoa! So, the value of the home increased by only 10%, but the value of your home equity just increased by 50%!

If you were to sell the home now (let’s ignore transaction costs for now), you would:

- Receive $1.1M in cash

- Pay off your $800,000 mortgage

- Have $300,000 left over for you

And you had put in only $200,000 of your own money (your down payment, that initial equity amount). Major return!

How can that be? Leverage, that’s how. You contributed only a fraction of the value of the asset in your own money and borrowed the rest.

Now, please note that using lots of leverage really hurt people in the real estate crisis of 2007-2009.

People thought that because real estate values only ever go up (of course, right?), they should put as little money down as possible in order to buy property after property after property. Maximize your leverage! Get rich!

Well, leverage helps in a market that is increasing in value. But it is equivalently devastating in a decreasing market. So, I am in no way recommending you go bonkers on the mortgage/leverage front. I’m just using this as a way to illustrate the power of stock options.

Leverage in stock options: Your exercise price!

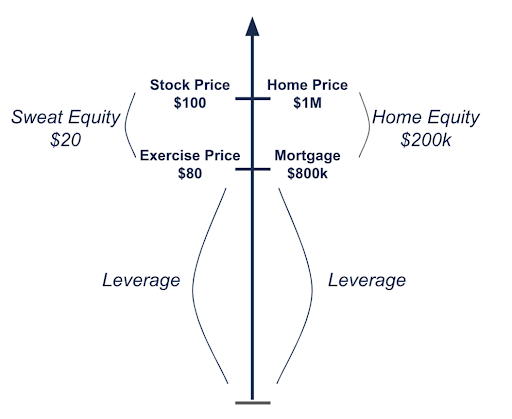

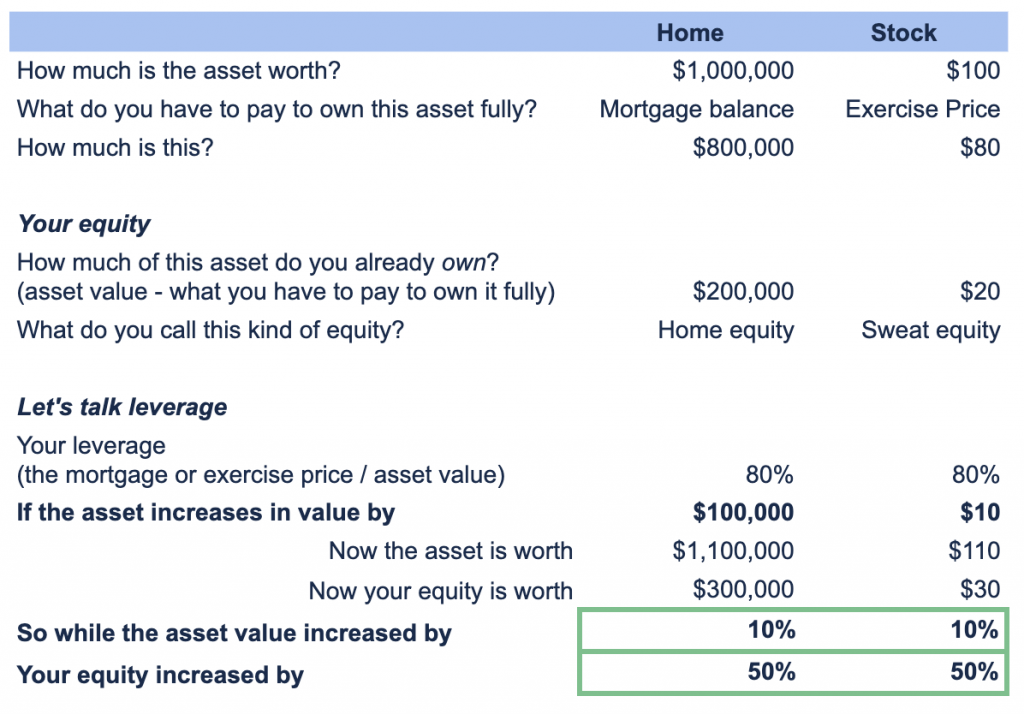

I’ve “mapped” all those elements of buying a home (with a mortgage) to having stock options (which have an exercise price), because they are logically the same.

The only things that are different here are that:

- A home is worth a lot more than a share of stock, so the scale of all the numbers is different. Here I’ve chosen a $1M home and a $100 share of stock.

- We use different words to describe home-related stuff than we do stock-related stuff

We’ll get into details in a second, but let’s start with an image to compare the two:

How does my leverage change? And what does that mean?

Your leverage changes as a result of the asset—home or stock—changing in value, up or down.

Let’s start with probably the simpler example: When it comes to your home, your home equity increases if the price of your home increases.

Equivalently, when it comes to stock options, your sweat equity increases if the stock price increases. This is what we illustrated above.

Leverage is just the inverse/opposite of equity, so as the price of the home or stock increases, and your equity increases along with it, your leverage decreases. As you can see, then,

decreasing leverage is a good thing, because it means your (sweat) equity is increasing!

When it comes to stock options, you could think about it like this:

- You start at a company when the stock is worth $100.

- You are granted an option whose exercise price is thus $100.

- You have sweat equity of $0 and leverage of 100% in that option.

- You work your butt off to help the company out* (aka, to build sweat equity) and the company’s stock price increases to $150.

- Now your sweat equity has increased to $50 ($150 stock price – $100 exercise price), and your leverage has fallen 67% ($100 exercise price / $150).

* I am far too cynical to buy into the notion that “Hey, your individual effort will help raise the company stock price, which benefits you” but that’s usually how it’s pitched so I use it here for its appealing logic.

Now, of course, if the stock price falls, the opposite happens:

- Your sweat equity shrinks (it can even turn negative if the stock price falls below the exercise price)

- Your leverage increases

Who cares what my leverage is? How does this help me decide when/whether to exercise my NSOs?

The amount of leverage you have in a stock option determines whether you should sell or hold.

Obviously (I hope?), if the exercise price were $0 (0% leverage), you should exercise today because you could own the stock for free.

If the exercise price were $100 and the stock price were $100 (100% leverage), then you should not exercise, because you’re not getting any value out of the option. You might as well buy the stock on the open market.

So, at what point between 0% leverage and 100% (or higher!) leverage does the decision switch from “You should exercise” to “Don’t exercise”?

As a reminder, with a stock option, calculate leverage like this:

Leverage = Exercise Price / Stock Price

Leverage > 40%: Don’t exercise.

Let’s go back to the example above, where your leverage is 80%.

This means that, by sitting there doing nothing, not putting a single dollar of your own money at risk, this thing you own—the stock option—can increase wildly in value with only small increases in value in the underlying asset (a share of stock). The value of the stock increases by $10 (10%), and the value of the stock option increases by 50%. Nice.

As soon as you exercise the option, you simply own a share of the stock outright. No more leverage.

If the stock is worth $100 and goes up $10 in value, then the value of the thing you own—now the share of stock—increases by 10%. No longer that sweet sweet 50%. And you lose your own money if the stock price falls.

Why would you put your money at risk in order to own something whose rate of growth is so severely constrained? I mean, when you have the alternative of sitting on your butt participating in all of the upside and none of the downside? That’s the holy grail of investing right there…All return, no risk, lots of butt sitting.

So, if your leverage is high, I’ll say over 40%, don’t exercise.

Smarter brains than mine came up with this 40% threshold. (I learned about it from advisors at Abacus Wealth Partners.) There’s some math behind it; I wave my hand dismissively. All I care about is that it’s “kinda high” versus “kinda low.” The rightness of the decision is based on future stock prices, which, of course, we don’t know, so “high-ish” and “low-ish” seem good enough to me. If you want to say 30% or 50%, fine.

Leverage > 100%: Really don’t exercise

If your exercise price is higher than the stock price, that will create a leverage of greater than 100%.

For example:

- Exercise Price = $110

- Stock Price = $100

- Leverage = 110%

This is what’s known as having an “underwater” option. Such an option is useless to you. For now. You could buy the stock on the regular ol’ stock market for cheaper. It might be worthwhile in the future, but please don’t exercise it now. Just hold on until it actually has value or it expires, which would suck, but it can happen.

Leverage < 40%: Exercise

So far it’s been all “don’t exercise!” But the ultimate goal is to have real money, so you have to exercise at some point. When is that?

A rule of thumb is to exercise—and sell!—the option when leverage gets under 40%.

What would this look like?

- You start at a company when the stock is worth $100.

- You are granted an option whose exercise price is thus $100.

- You have sweat equity of $0 and leverage of 100% in that option.

- The company’s stock price increases to $260.

- Now your sweat equity is $160 ($260 – $100 exercise price), and your leverage is 38% ($100 exercise price / $260).

So, you could reasonably start exercising and selling.

Leverage isn’t the only consideration.

Leverage is a really important consideration when trying to figure out if you should exercise your options or not. It is not, however, the only important consideration.

- How much of your wealth is tied up in this company stock, both in outright shares and options? Even if it’s all in options (i.e., none of your own money is at risk yet), if the company’s stock takes a long-lasting nose dive, then the value of your options do the same…and your net worth is very much the worse for it. Which is to say, if much of your wealth is wrapped up in company stock, that suggests selling some, which could involve exercising and selling options.

- Do you need the money now or soon? Even if the leverage is higher, but you could use the money right now to buy the house of your dreams, or take a sabbatical that your mental health desperately needs…that could be a cost worth incurring to improve your life Right Now.

- Do the options expire soon? Are they near the expiration date? As long as the exercise price is one penny under the current stock price, it’d be worth exercising them instead of letting them expire.

- This includes the scenario in which you want to leave the company, and your departure will trigger a 90-day window for exercising—or losing—your options.

- You can find the expiration date on the grant document and also in the stock plan administration website. In our firm, we actually record reminders in our calendar for the upcoming expiration of all our clients’ stock options just so we’re sure not to miss their expiration. You can do the same!

If you want to get a bit nerdier about it (oh, it’s turtles alllll the way down, people), here are some great resources:

- https://stockopter.com/timing-employee-stock-option-exercises/, which introduces the idea of an Insight Ratio®, which is similar to the leverage calculation, but more complicated and robust, as it considers factors like time to expiration and the volatility of the stock.

- https://stockopter.com/nqso-no-no/, which explains why, if you exercise a non-qualified stock option in a public company, you really should sell it ASAP, not keep it for a year in order to get long-term capital gains treatment

Do your non-qualified stock options just sorta sit there in your head, persistently occupying space because you don’t know what to do and are afraid of making the Wrong Choice? Reach out to me at . I am happy to put you on our waitlist or give you referrals to other, wonderful planners.

Sign up for Flow’s weekly-ish blog email to stay on top of my blog posts and videos.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for general information and illustration purposes only. Nothing contained in the material constitutes tax advice, a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, or investment advisory services. I encourage you to consult a financial planner, accountant, and/or legal counsel for advice specific to your situation. Reproduction of this material is prohibited without written permission from Meg Bartelt, and all rights are reserved. Read the full Disclaimer.