Big tax changes are a’ comin’. Maybe. In our last blog post, I discussed one big strategy to take advantage of the possible expiration of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act: the fabled Roth conversion.

The TCJA went into effect on January 1, 2018. All of the TCJA’s changes to tax law will expire at the end of 2025—and tax rates and other rules go back to the pre-2018 levels—unless Congress renews it.

In this blog post, let’s cover a few more strategies that might end up being really helpful to have done if the TCJA does indeed expire. But remember, because we don’t know whether the TCJA tax laws will expire or be renewed, you only want to make moves now if you’ll still be okay regardless of whether Congress renews it or lets it expire. Don’t go bettin’ the farm on Congress doing or not doing something.

And as with the previous blog post, it’s going to be Very Helpful to have a competent CPA on your team to help model the tax impact of any of these strategies.

Exercising Non-Qualified Stock Options (NSOs)

Remember how (and if you don’t, go back and reread our last blog post) I recommended that you consider converting pre-tax money in your IRAs or 401(k)s to a Roth account, because tax rates are low now compared to what they will be if the TCJA expires? And we want to incur taxable income when tax rates are lower?

Well, the exact same logic applies to the idea of exercising non-qualified stock options (NSOs).

When you exercise an NSO, you immediately owe income tax on the “spread” between the exercise price and the value of the stock.

Let’s say you exercise one NSO at a strike price of $1 with a share price of $10 (be that the price on the stock market for a public company, or the 409(a) value for a private company). That gives you $9 of taxable income.

Most people aren’t thinking about just one option. So, let’s think about 10,000 NSOs. In the exact price scenario above, you’d immediately have $90,000 of taxable income.

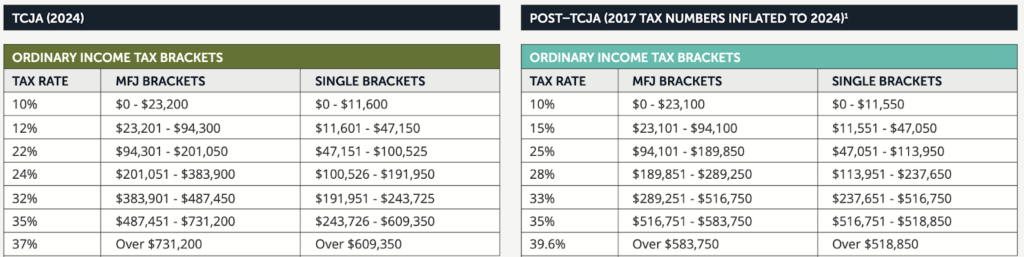

Behold the tax brackets and tax rates below, which is what they are now, and what they will be if the TCJA expires. Imagine that you’re single and your salary + bonus is $500k/year. If you exercise NSOs now, that generates an extra $90k of taxable income, all of that will be taxed at 35%. If you exercise post-TCJA expiration, then a little of that $90k will be taxed at 33%, a little at 35%, and most of it at 39.6%. Which, let’s review, is higher than 35%.

If you look long enough at the chart below, you can see that in some income scenarios, you’ll actually have a lower top tax rate post-TCJA than now. You’d need to run the numbers for your own specific situation to make sure.

Consider doing this: Exercise NSOs now, especially in private companies, if it would generate taxable income in a lower tax bracket than post-TCJA expiration. If you have NSOs in a public company, I’m usually of the opinion that you shouldn’t exercise NSOs until you’re ready to exercise and immediately sell, and that having the right amount of leverage is a good tool for determining when to do that. That’s probably still more important than gaming tax rates.

Exercising Incentive Stock Options (ISOs)

Surprisingly, most people I talk with who have ISOs seem to know about Alternative Minimum Tax. (Someone out there has been doing some good employee education!) The understanding sometimes stops right there: this tax exists, it’s related to ISOs, and, uh…tax bad?

For a short primer/reminder on AMT, read this blog post, the section entitled “Mistake #3: Forgetting about Alternative Minimum Tax on ISOs,” from our friends at McCarthy Tax.

What’s important in this blog post here is that the likelihood of having to pay AMT when you exercise ISOs will go up dramatically if the TCJA expires. You can usually exercise some ISOs without triggering AMT because there’s an “exemption” amount of AMT income before the tax kicks in.

Let’s say you exercise one ISO at a strike price of $1 with a share price of $10. That gives you $9 of AMT-eligible income. That income will likely not be subject to any tax because it’s below the exemption threshold.

At the other extreme, let’s say you exercise 100,000 such options, for $900,000 of AMT-eligible income (and then you hold the shares for at least a year). Yeah, you’re likely going to have to pay AMT.

You want to be pretty clear on where the tipping point is from “I don’t owe AMT” to “I owe AMT.”

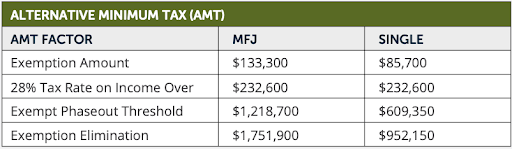

That tipping point is determined in large part by what the AMT exemption amount is. The higher the exemption amount, the less likely you will have to pay AMT on your ISO exercises. You can see in the table below that right now, you can incur $133k of AMT-eligible income (as a couple; $85k as a single person) before triggering the tax. That threshold will drop meaningfully if TCJA expires: drop by roughly $29k for married couples filing jointly and roughly $19k for people filing taxes as Single.

Okay, what are you supposed to do with those numbers? Let’s continue with the example just above.

You can incur roughly $19k more AMT-eligible income now than you would be able to under the rules if TCJA weren’t in effect (all else held equal in your tax situation). So, with $9 of AMT-eligible income per option exercised, you could exercise roughly 2000 more ISOs now without triggering the Alternative Minimum Tax bill, than if you were exercising under tax rules without the TCJA in effect.

So, yes, you still have to pay the exercise price on that extra 2000 options (i.e., $2000, in this example), but you don’t have to pay anything more in taxes. Pretty sweet, eh?

Consider doing this: If you’re sitting on some exercisable ISOs (most likely that means they’re vested, but it could also mean you have early exercise/83(b) exercise available to you for unvested options), exercise ISOs now, up to the currently-higher AMT exemption limit.

Yes, you’re still putting your exercise price money at risk…but you’re not putting any money at risk paying taxes. You have up until the end of the year to do this. And then again in 2025.

[Note: Paying AMT isn’t the end of the world. If you pay it, you now have an AMT credit in your tax return, and if you make sure to carry it forward onto all subsequent tax returns, you have a chance of using that credit up in future years, thereby “getting back” any excess tax you paid in your AMT year. But, you know, it’s still nice to avoid paying it in the first place, as receiving the credit back isn’t guaranteed and also $1 now is better than $1 in 5 years. If you want to learn more about the AMT credit, see this blog post, the section “Mistake #4: Forgetting about the AMT Tax Credit”]

Increase your ability to exercise ISOs without AMT by increasing your ordinary income.

The higher your ordinary income, the higher your AMT income can be before triggering the tax. (This fact is independent of this TCJA discussion.) And increasing your ordinary income—by pulling future income into this year or 2025—might be a reasonable strategy to pursue in and of itself because your tax rates might be lower now than later.

What are some strategies for increasing your ordinary income?

In the tech world, it’s usually if you have non-qualified stock options to exercise. As discussed above, the spread between the strike price and share price is taxable ordinary income in the year you do the exercise. So, exercise more NSOs. Pay taxes on those (maybe at a lower tax rate than you’ll have in the future?) and then exercise even more ISOs without triggering AMT.

If you have any self-employment income or any other income whose timing you have control over, you could also consider accelerating income earlier rather than in later years.

Delay charitable contributions

The primary reason you should donate to charity is that you want to give money to a deserving cause or person. If you want to keep on keeping on in your annual charitable contributions, I APPLAUD YOU.

But if you’re already going to donate, you might as well make it as tax efficient as possible, eh?

There are two reasons that delaying charitable contributions might save you taxes:

#1 You save more when tax brackets are higher. If you are currently at a 37% tax bracket (the highest current tax rate) for every dollar you donate to charity (and itemize on your taxes), you save 37¢, which means it costs you 63¢ to donate that dollar. If you are at a 39.6% tax bracket (the highest rate in a post-TCJA world), you save 39.6¢ for every dollar you donate to charity, which means it costs you 0.604¢ to donate that dollar to charity.

Purely from that perspective, it makes sense to donate money in years when you’re in a higher tax bracket.

If you think tax brackets could rise in 2026, maybe it’d behoove you to delay charitable giving until 2026, when you could “bunch” charitable contributions from 2024, 2025, and 2026 into 2026. That way you’d get the benefit of bunching (a strategy that can be useful no matter what the tax-rate regime) and you’d be saving taxes at higher tax rates.

I wrote a series of blog posts about creating my family’s charitable giving plan, and it covers tactics we employed to make it more tax efficient, like donating “appreciated securities” instead of cash and the just-mentioned “bunching” of multiple years’ worth of donations into one year.

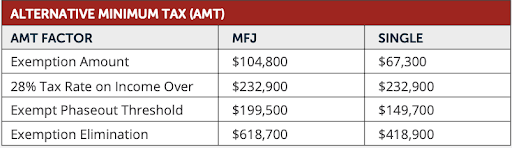

#2 You’re more likely to itemize—and actually get tax benefits—if TCJA expires. Also changing if TCJA expires is the standard exemption: it’d go down a lot:

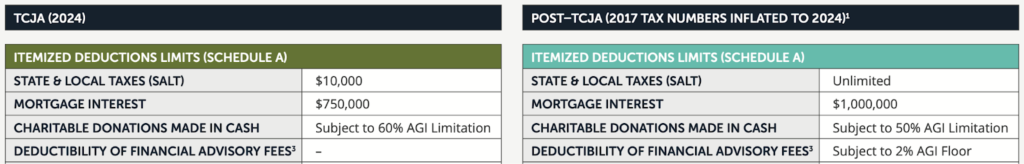

You also will be allowed to itemize much more of what are often people’s two biggest expenses: mortgage interest and state and local taxes.

Right now, you can itemize interest on mortgages only up to $750k. That’d change to $1M. (And in places like the Bay Area and NYC, it’s reeaaaaallll easy to get a mortgage that big.)

Secondly, right now you can deduct only $10k of your state and local taxes (known as SALT). Again, if you live in California or NYC, your state and local taxes are likely way more than that.

Thirdly, and probably less impactfully, is that you could once again deduct the fees associated with using an investment advisor. (Thought I’d throw that in there for, you know, self-promotion’s sake.)

So, now you have a lower standard deduction and you’re being allowed to itemize more things, meaning it’s easier to get to the point where it’s worthwhile to itemize deductions because they exceed the standard deduction.

Consider doing this: Delay your charitable contributions to 2026. Between potentially higher income tax rates at that point, and the increased ease of itemizing deductions over taking the standard deduction, this could save you meaningfully in taxes.

Please return to my first comment in this section: the primary reason to donate money is to help people or causes, not to save in taxes.

If you're high net worth, get more assets out of your estate.

There’s too much to think about here, for this one blog post. I would absolutely encourage you to talk about this with your estate planning attorney (and/or your financial planner) .

What’s going on? When you die, any money in your estate above a certain threshold will be subject to a federal estate tax of up to 40%. (Look here for details. Some states also have estate/death/inheritance taxes, but we’re not discussing those.) Right now, that exemption is $13,610,000 per person. If TCJA expires, it’ll drop back down to what is currently estimated at $6,810,000.

Which means that if you have $10M now and die, your estate won’t have to pay any estate taxes and your heirs get all your money. If you were to die in a TCJA-expired world, $3,900,000 of your estate would be subject to estate tax, and your heirs would lose a lot of money to estate taxes.

Maybe you don’t have $10M now. But, you do have $5M, and if you live another 20+ years, and that money is invested and grows, you will have a bunch of money when you die. And then your heirs could still miss out on a lot of money because of estate taxes.

In either case, the overarching strategy being widely discussed now is to move money out of your estate now, when you have that big ol’ $13,610,000 lifetime exemption available to you. You can move your money out of your estate in a variety of ways, from plain vanilla (like funding your child’s 529 college savings account) to more complicated (like family limited partnerships and Nevada Asset Protection Trusts…no, I don’t actually know how these work, I’ve simply spoken with estate planning attorneys who do).

There is so much more to this discussion. Way more information is necessary from attorneys far more knowledgeable than I. This mention is only an amuse-bouche.

The benefits of moving money out of your estate now are the more obvious: Possibly saving your heirs a lot of estate tax.

In my opinion, there are a couple of major downsides to moving money out of your estate now:

Complexity: Your financial situation is almost certainly going to get more complex, with more accounts or legal structures to keep track of, and possibly changes to how you access your money/get income. Simplicity is worth fighting for.

Reduced access/flexibility: Your access to your money is almost certainly going to be more constrained, and possibly just outright reduced. Moving money out of your estate more or less means that it’s no longer yours to control and use as you want.

I believe that the younger you are, the more important this is to consider. With so many years of life ahead of you, life is nothing but Uncertainty. Flexibility is a powerful tool in such circumstances.As one of my favorite estate planning attorneys observed, you might want to retain all your money unencumbered because, who knows! You might want to emigrate to a different country, buy your own baseball team, start a business, or start a foundation. And who knows what kind of adult your three year old is going to turn into in another two decades.

If you’re 80 and have 10, maybe 20 years left, this decision is one thing. But if you’re 40 and have two young kids and have half a century of life unfolding in front of you? Putting any of your money out of your control is, in my opinion, a risky gambit.

To boot, who knows what estate rules will be when you eventually die (hopefully, decades from now, by which time Congress will likely have changed the rules another 10 times)?

Consider doing this: Talk with an estate planning attorney who is familiar with the strategies necessary to move money out of your estate. But do this well before the end of 2025, because they are going to be slammed by then! It’d be like trying to hire a CPA in March to do your taxes by April 15. By which I mean: Good luck with that, yo.

Blog posts like this actually make me a bit anxious. There’s so much finicky stuff to keep on top of! I can only imagine how thinking about this must affect people who aren’t financial planners.

Just try to keep in mind that these strategies are not the essence of personal finance. The essence of personal finance is: spend less, save more, and don’t do anything stupid (according to Dick Wagner). If you’re not doing those things yet, focus your effort there first!

Would you like to work with a financial planner who can help proactively identify opportunities like this and then figure out whether they’re useful for you and your finances? Reach out and schedule a free consultation or send us an email.

Sign up for Flow’s twice-monthly blog email to stay on top of our blog posts and videos.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational, general information, and illustration purposes only. Nothing contained in the material constitutes tax advice, a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, or investment advisory services. We encourage you to consult a financial planner, accountant, and/or legal counsel for advice specific to your situation. Reproduction of this material is prohibited without written permission from Flow Financial Planning, LLC, and all rights are reserved. Read the full Disclaimer.