What if you didn’t have to save more than you already are, if you didn’t have to change what you invested in…and you could still get more money out of your investment portfolio? Pretty nice, eh? Well, you can.

May I introduce asset location.

Asset location is an investment strategy that puts certain types of investments into certain types of accounts based on the investment’s tax characteristics and the account’ tax treatment. The goal is to create larger after-tax returns for your investments. “After-tax” is the money you can actually spend. Pre-tax numbers are simpler to understand…but not as useful.

Vanguard estimates that proper asset location can increase after-tax return by 0..05 to 0.3% each year. Sounds…kinda small. But if you compound that over years, and talk about it in dollars and not percentages, it can sound…kinda big.

In this post, I’ll describe a lot of the nitty gritty of asset location, and I’ll end with how we use it here at Flow for our clients’ investment portfolios.

This Is the Icing, Not the Cake.

You do not need asset location to be a successful investor. It is icing on the investment cake. That cake’s ingredients?

- Broad diversification. Owning not 1 stock or 10 stocks, but 1000 stocks.

- Low cost

- An appropriate “asset allocation” for the amount of time until you need the money. That is, the balance of stocks and bonds in your portfolio. Yes, we’re talking asset ALLOcation vs. asset LOcation. Sorry about that! I don’t pick the names!

(You can learn more about our beliefs about what constitutes good investing, in this blog post.)

To boot, the younger you are and the smaller your investment portfolio, how much you save is usually more important than all those things.

But if you’ve already got the cake, and you’ve got the personal wherewithal to ice the cake, or if you’re working with a financial planner whom you’re paying to ice the cake, then yeah, let’s do this thing.

The Rules of Asset Location

Here are the rules that govern asset location:

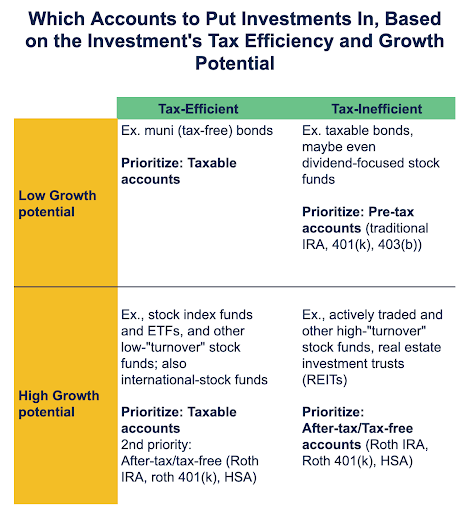

Rules based on tax-efficiency:

- Put your tax-efficient investments in your taxable accounts.

For example, a total US stock market index fund. “Tax efficient” means your investment doesn’t produce much investment income (interest, dividends, capital gains distributions) during the year. - Put your tax-inefficient investments in an IRA or 401(k) (or other tax-protected account).

For example, a taxable-bond fund.

Rules based on growth potential:

- Put low-growth investments in a traditional IRA or traditional 401(k) (or other pre-tax account).

For example, a total US bond-market fund. - Put high-growth investments in a Roth IRA, Roth 401(k) or HSAs (or other after-tax or tax-free account).

For example, an S&P 500 fund.

One more rule that doesn’t fit neatly above: Put international-stock funds in taxable accounts. These funds typically pay foreign taxes, and if you hold them in taxable accounts, you can get a foreign-tax credit for those taxes paid, reducing your US taxes. If you hold them in a tax-protected account, you can’t get that credit.

Put ‘em together and what have you got?

Bippidi boppidi…oh wait, no.

You get a decision matrix like this:

Why Does Tax Efficiency Matter?

If you were retired, it’s possible that having investments producing income throughout the year wouldn’t be a bad thing. You’ll need money to live on, after all! You can use that investment income (interest, dividends, fund distributions) as that income.

But if you’re still working, your job provides all the income you need (god willing). You don’t want to have to pay taxes on income you don’t need. So, we want to minimize taxable income coming from your investments.

Which means we put tax-efficient investments in an account where you do pay taxes, because those investments won’t create much taxable income. And we put tax-inefficient investments in accounts that are tax protected, because regardless of how much income your investments create, you don’t owe taxes on it.

Why Does Growth Potential Matter?

Because we want to minimize the bucket that the government can take taxes out of and maximize the bucket that you own 100% yourself.

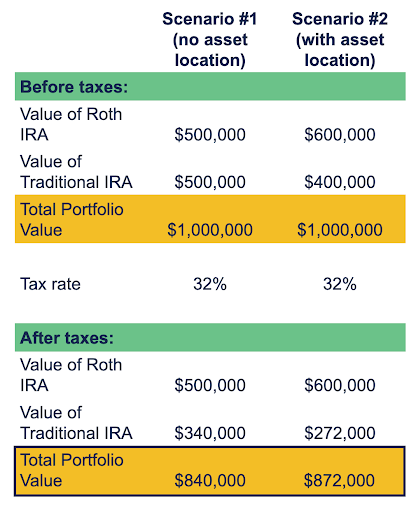

Let’s say you retire and have a $1M portfolio. The after-tax size of your portfolio varies depending on how much of your portfolio is in a pre-tax IRA vs. a Roth IRA. The bigger your Roth IRA is relative to your pre-tax IRA (for the exact same total portfolio balance!), the more money you will have to spend.

In this chart, you can see that when the $1M is split evenly between a Roth IRA and a traditional IRA, your after-tax portfolio is worth “only” $840k. (We’re assuming a marginal (i.e., top) tax rate of 32%.)

But let’s say you used asset location over many years, putting your high-growth investments in a Roth IRA and your low-growth investments in a pre-tax IRA. As a result, your Roth IRA is worth $600k, and your traditional IRA $400k. In this scenario, your after-tax portfolio would be worth $872k. Same $1M total portfolio…but a bigger Roth bucket gives you more money to spend.

Follow these rules gently, not obsessively.

These are guidelines. You can get a lot of the benefit of asset location by adhering only loosely to these rules.

You don’t have to put all your stock holdings in a Roth or even taxable account. It’s okay to have some in a pre-tax IRA! Just get a good chunk of your stock holdings (especially if they’re tax inefficient) in your Roth IRA to increase your lifelong tax savings.

Balance Optimization (Icing) with Simplicity

Asset location is easy enough to do, at a high level.

The more narrowly defined your investments, the more exacting you can get in your asset location…but at the cost of portfolio simplicity. So, I’m not sure you should get that exacting.

For example, a high-level implementation of asset location would mean getting most of your stock investments into a Roth IRA and most of your taxable bond investments into a traditional IRA.

In contrast, let’s say you break your portfolio down into individual stocks, commodities, micro cap US stock funds, small cap, mid cap, large cap, both growth and value, equivalent complexity on the international front, private-company stock, cryptocurrencies, etc. You now can pick the best account for each of those 10+ types of investments to go into. That’s harder to set up in the first place and harder to maintain.

I recommend getting most of the value of asset location with the least amount of setup and maintenance required. Asset location is optimization enough unto itself. I don’t believe you need to optimize the optimization.

The Challenges of Asset Location

An asset-location strategy is a multi-year (-decade) commitment. As with pretty much any investment strategy, there are challenges that you should really think about before you commit to it.

Each Account Will Perform Differently.

I used to work at a financial advisory firm that did not use asset location. They invested all of a client’s multiple accounts the same.

If the client’s target asset allocation was 90% stocks/10% bonds, then by gum, their taxable account was 90% stocks/10% bonds, their pre-tax IRA was 90% stock/10% bonds, their Roth IRA was 90% stocks/10% bonds…and all the spouse’s accounts were also 90% stocks/10% bonds.

I asked the lead advisor one day why they didn’t use asset location. He explained (I paraphrase) that a lot of clients couldn’t handle the fact that each account would perform differently than the others, and that their spouse’s accounts would also perform differently than theirs.

Your all-bond pre-tax IRA would grow 3% in a year, and your spouse’s stock-heavy taxable account would grow 16% in one year. Or one loses 3% while the other loses 20%. That doesn’t feel good.

Asset location is a portfolio-level strategy, not an account-level strategy. That means you have to be prepared for each individual account to perform differently. Your focus should be on The Total Portfolio. How did all your accounts perform together?

Big Money Movements In and Out of an Account Can Create a Challenge.

Let me tell you a story about difficulties we ran into when implementing asset location in a client’s portfolio.

We were managing this client’s Financial Independence (aka Retirement) portfolio, which consisted of a taxable account, a traditional IRA, and a Roth IRA. The portfolio’s asset allocation was 85% stocks/15% bonds. As prescribed by the basic asset location rules, all her bonds were in the traditional IRA.

Then we helped her roll that traditional IRA money into her 401(k) so that we could do a backdoor Roth IRA for her. Now, with her IRA emptied out, her asset allocation was…100% stocks. Eeek.

We needed more bonds. How to get them? We had two types of accounts to put them in: her Roth IRA and her taxable account.

I didn’t want to put them in her tax-free Roth IRA, as that’s the account where I want to put our “growthiest” possible investments.

That left her taxable account. But in order to buy more bonds, I’d have to sell some of the existing stocks, creating a taxable gain. She’s mid-career as a director at a big tech company. She’s earning a bunch of money, at a very high tax bracket. I really don’t want to create capital gains taxes if possible.

In her case, thankfully and coincidentally, around the same time, she received a gift from a family member of a bunch of a single stock. Whenever a client has a concentration in stock like that, we create a diversification strategy. In this case, part of that strategy was to use the sales proceeds to buy bonds.

You can perhaps see how, if she didn’t have the luck of that big gift, we likely would have ended up doing something “suboptimal” in either her taxable account or her Roth IRA in order to achieve the more important target of getting bonds back into her portfolio (i.e., getting her asset allocation back on target).

This same thing can happen when you do a big Roth conversion. Before the conversion, you have all sorts of pre-tax money, and you can hold bonds there. After the conversion, you have less pre-tax money and more Roth money. How will you make sure that the portfolio’s asset allocation is still on target?

It Makes Your Investments More Complex.

One benefit to investing all your accounts the same way is that, if you put more money into an account or take money out of an account, it’s easy to figure out how that account should be invested with its new (higher or lower) balance: The exact same as it was before. Was it 90% stocks/10% bonds before? It still is.

If you use asset location, every time you add a lot of money to or take it out of an account, or every time you do your annual “rebalancing” of your portfolio, you have to figure out how to change the asset allocation in each account to ensure that the total portfolio’s asset allocation is still correct (remember, the asset allocation is more important!), while still obeying the basic rules of asset location.

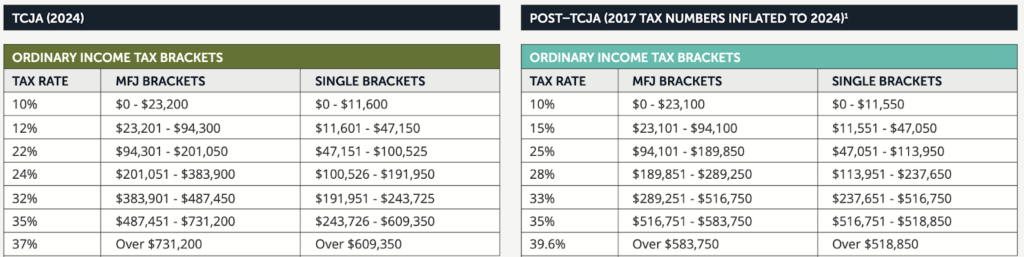

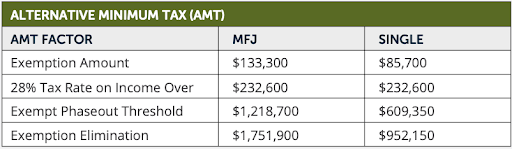

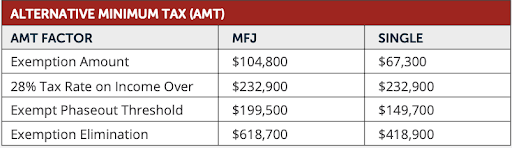

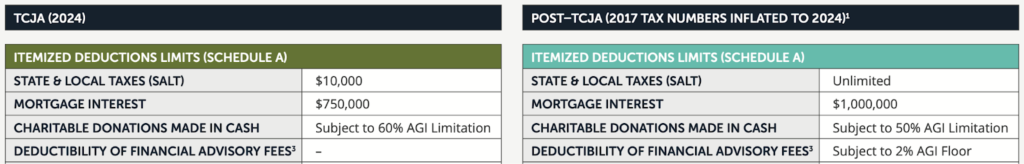

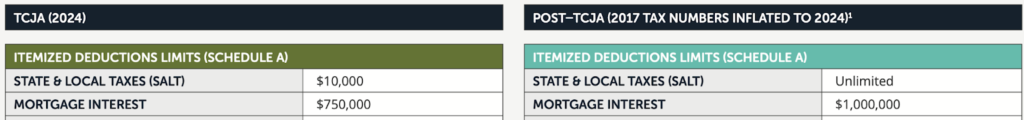

Tax Laws Can Change, Undercutting the Value of Asset Location.

The value of asset location comes from the fact that you have to pay taxes on investment income and withdrawals from pre-tax accounts. The higher the taxes, the bigger the value of asset location.

As tax law changes, asset location could become less valuable. (Of course, it could go the other way, too.) Certainly, if tax rates fall, asset location becomes less valuable. Already, the value of putting real estate investment trusts (REITs) in tax-protected accounts (IRAs, 401(k)s, HSA) isn’t as great as it used to be, because now you can get some tax benefits by holding real estate in a taxable account.

What We Do at Flow

At Flow, in our clients’ portfolios, we follow the good ol’ 80/20 rule: we want to get 80% of the benefits of asset location with 20% of the work (and complexity).

Here’s our focus:

- Roth IRAs and HSAs get stock funds.

- Pre-tax IRAs get taxable-bond funds.

- Taxable accounts get everything else.

- If we need more bonds in the client’s portfolio, we’ll often use tax-free (aka, muni) bond funds in the taxable account.

- We use broad market index funds, so all our stock funds are tax efficient, whether they’re here in the taxable account or in the tax-protected Roth.

This strikes me as a good balance of simplicity and tax optimization. Other advisors with good investment philosophies and implementations do it differently. As I’m fond of quoting:

“There is no perfect portfolio. There are many perfectly fine portfolios.”

Do you want your investments managed in a way that balances optimization with your ability to understand what’s going on? Reach out and schedule a free consultation or send us an email.

Sign up for Flow’s twice-monthly blog email to stay on top of our blog posts and videos.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational, general information, and illustration purposes only. Nothing contained in the material constitutes tax advice, a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, or investment advisory services. We encourage you to consult a financial planner, accountant, and/or legal counsel for advice specific to your situation. Reproduction of this material is prohibited without written permission from Flow Financial Planning, LLC, and all rights are reserved. Read the full Disclaimer.