I’ve been thinking about this blog post for over a month now.

Despite starting to think about it such a long time ago (by blogging standards), and despite generally being not at a loss for words, I found myself struggling to write about this last year in business.

[Note: We celebrate Flow’s birthday on May 9. If you want, read my Year 8, Year 7, Year 6, Year 5, Year 4, Year 3, and Year 2 reflections.]

Eventually I realized, Duh, Meg, you’ve had a physically, psychically, and emotionally exhausting 2025 so far. You just don’t have the energy to write your “usual” blog post.

Prior to last December, my business was stable, which was actually kinda…uncomfortable for me. My business coach counseled me to practice “tolerating the shit out of your success.” I was busy experimenting with this novel idea when December hit.

In December, my stage 0 breast cancer—for which I’d had two lumpectomies and radiation in 2023 and 2024—came back. I had a (single) mastectomy in early March, followed by convalescence for the rest of the month. And since then, I have been catching up.

I don’t want to belabor the whole experience, so let me share something important I took away from it:

It’s Really Nice to Let People Care for You

I often hear from people that it’s hard for them to accept help. When I was preparing for my mastectomy, my OOO, and my recovery, I made a conscious decision to embrace the shit out of letting people help me.

And it. was so. lovely. (10/10, would recommend)

My colleague, Jane Yoo, stood ready to help my clients with any urgent financial planning needs during my convalescence. (I still haven’t figured out a thank you gift that reflects the huge impact of your support, Jane. Sorry!)

My Client Service Associate Janice worked diligently to keep communication going with clients and pushing work forward in my absence.

Clients expressed concern in meetings and via email.

Local colleagues and friends brought my family meals.

Remote colleagues and friends sent us meal kits and Door Dash cards. And even the occasional t-shirt with “Thank fuck that’s over” emblazoned, conveniently, right over the breast that I had removed.

(My husband was all, “Jesus, Meg, how many people do you know?” To which I responded, It’s nice to be a woman. We support each other really well.)

Most important of all, my husband. He made the family “run” throughout it all. He made me feel loved and supported and not like a freakshow in the aftermath of the mastectomy. (Many parts of the whole experience were gross, and many more uncomfortable or painful. But the single worst experience was the first time I looked beneath the bandages just a few days after surgery. It took my breath away, but not in a good “Top Gun” sort of way.)

What Else Happened During My Ninth Year in Business?

I think Cancer and Mastectomy pretty handily trumps most other things. But other important things did happen!

We hired our own planner.

My husband and I hired our own financial planner. I had been our financial planner up until then.

Despite having enough of the technical knowledge to do the job myself, as I had been doing for years, I wanted to work with a financial planner for four reasons. I wanted:

- a thinking partner. Life is complicated, and getting increasingly so.

- a backup for me/for my family

- someone to put me first (as I put my clients first)

- someone to Identify my blind spots

Professionally, the whole process of interviewing financial planners and working with ours so far has been instructive to me, unsurprisingly.

Personally, we’ve only been working with him (yes, a man! <gasp>) since January, and I already feel the relief of knowing that someone is in my (our) corner, keeping an eye on things.

I established a formal emergency continuity plan for Flow.

One of the biggest challenges of starting an independent advisory firm is making sure your clients are taken care of if something happens to you (you die or become disabled).

I had been doing what I think most small, independent firm owners did: I arranged (informally) with a few colleagues to help serve my clients in the event I became unable to. The arrangement had meaningful inadequacies:

- These colleagues ran firms that probably wouldn’t allow them to assume relationships with all my clients, overnight. Which meant that many of my clients would have to be redirected elsewhere.

- My family wouldn’t get any monetary value out of this firm that I’ve spent nine years building.

The firm I now have a legal agreement with is big enough to accommodate all my clients, have a plan for how they’d do that, and sufficient expertise and compassion to serve my clients.

This was a very big deal for me, and I’m very glad it is finally done.

My Associate Planner left.

In mid-January, my associate planner left.

This meant I had to rejigger my plan to support clients before and during my medical OOO. ‘Twas stressful, but I got it done, and I’m quite proud of myself for how I navigated the whole thing.

Without an associate planner, I am back into alllll the weeds of financial planning. And I gotta say, it’s fun. I like the process of forming the “picture on the boxtop” from all the individual puzzle pieces of a person’s financial life. Diving back into the entire process has given me more opportunities to see what might be improved.

Leading up to my surgery, during my convalescence, and for these two or three months back in the office but “catching up,” I made the conscious decision to not think (much) about what to do about no longer having an associate planner. I simply need to “get through” (i.e., work a lot, but it is work I know how to do).

Once I am through this crush, I will raise my head again, like a curious meerkat, look at the expanse of my business and my life, and start thinking Big Thoughts again.

I continue to fall deeper in love with the Annual Renewal Meeting.

I learned from my former marriage therapist that “there is freedom in structure.”

After a client and I get past the first year’s hurly burly, the cornerstone of my client-service structure is the Annual Renewal Meeting. I love this meeting, and I love the structure I’ve created for it. My preparation is structured. My follow-up is structured. Which means I can find real “freedom” in the meeting itself; it can be largely guided by whatever feels most important for the client.

I love this meeting so much, I married it. Wait, no, I mean I wrote a whole blog post about it.

I found my professional home.

In 2023, five women business owners and financial planners who live in the Pacific Northwest got together in an Airbnb on the beautiful, dreary coast of Washington (or Oregon, I forget…they’re very close to one another!) for a long weekend business retreat in January.

In 2024, the group met again. Alas, I was starting radiation so couldn’t attend. But in 2025, I did! (We had a bra-burning party on my behalf—bras burn alarmingly easily—as I knew by that time that I’d have to have a mastectomy.)

That weekend was profound. It felt like we’d found a real “home” in the profession. Colleagues (and friends!) who could help each other improve. Celebrate each other’s accomplishments unstintingly. Laughingly demand, “Alright, who farted!” (It was me, okay? You’re the one who fed me lentils!) And also simply hold each other (sometimes literally, sometimes metaphorically) as we talked about hard things. This industry can be full of judgment and hardness. It’s nice to have a safe, soft landing spot.

As I left our 2025 retreat, I asked, “If what I’ve already built in this business is enough to enable me to have weekends like this in my life, why am I so anxious about building anything more or different?”

Looking Forward

Since December, I have had my head down and blinders on, intent on getting myself, my family, my clients, and my business through the entire surgery “thing.” As such, I don’t have any clear ideas about what’s next… other than dedicating time to figuring out what’s next.

Even though I started writing this blog post without much direction, now that I’ve written it, I realize that a big theme is connection and relationship.

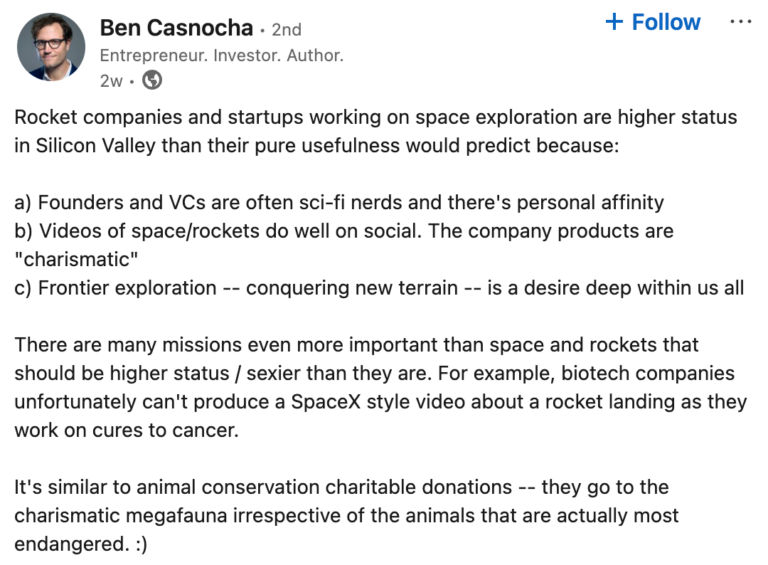

It reminds me of a favorite David Brooks opinion piece, in which he talks about the two mountains we climb in life. We climb the first when we’re younger, and on that mountain we try to achieve all the things that “society” tells us we should: money, career, awards, a home, etc. For people on the second mountain, “It’s not about self anymore; it’s about relation, it’s about the giving yourself away. Their joy is in seeing others shine.”

So, I sincerely hope that, whatever comes next, it’ll be less focused on measurement and more focused on connection.

Are you looking for a financial planner and don’t mind one who, at least once a year, does some serious navel-gazing?